No products in the basket.

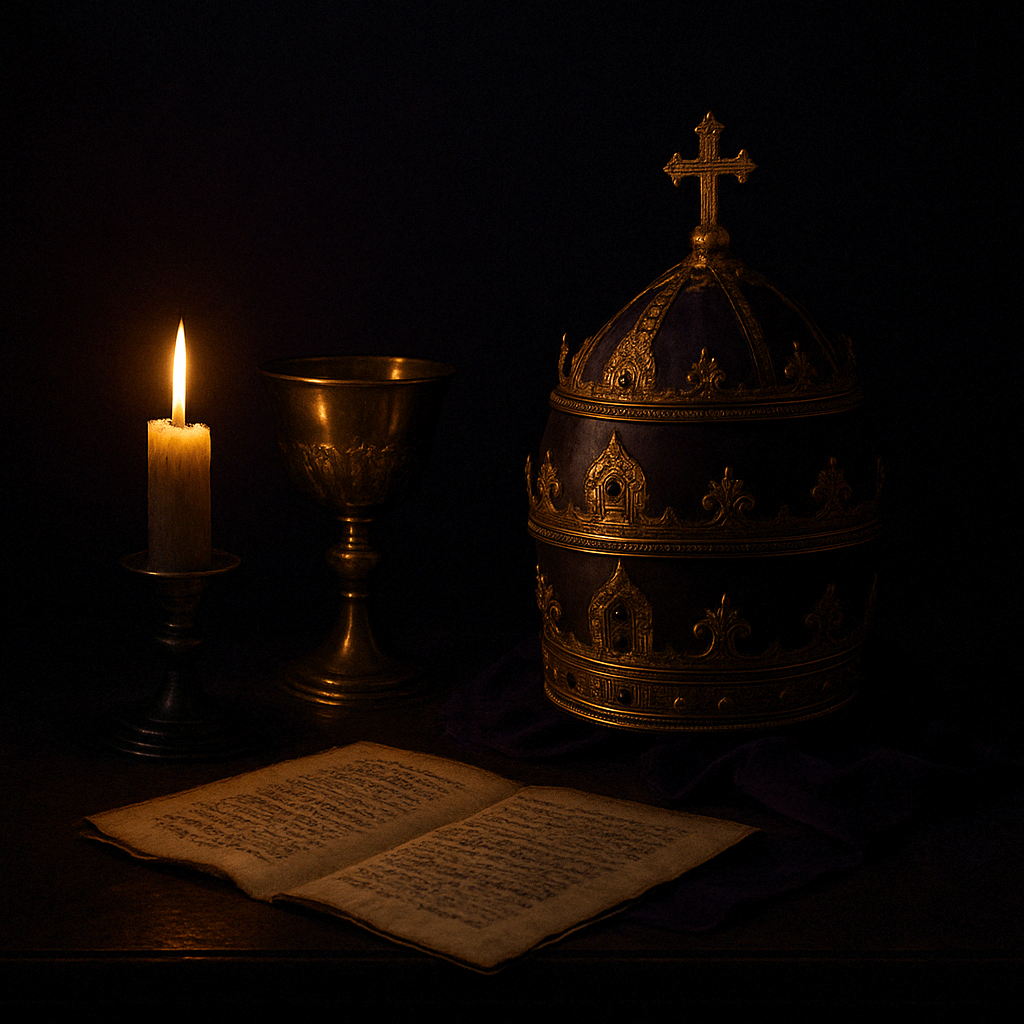

The Elemental Foundations of Astrology: An Exploration of Ancient Philosophical Underpinnings

Dear NightFall Astrology readers,

Astrology, a practice that has shaped human thought for millennia, is the product of a rich tapestry of cultures and traditions. Its origins can be traced back to the ancient civilsations of Mesopotamia, where the earliest forms of astrological thought were developed. Babylonian scholars, meticulously observing the heavens, began to discern patterns they believed were linked to earthly events. Concurrently, in the fertile Nile delta, Egyptian priests and astronomers formulated their own methods for interpreting the movements of celestial bodies. These two great traditions, Babylonian and Egyptian, would eventually merge, laying the groundwork for a new form of astrology.

The synthesis of Babylonian and Egyptian astrology occurred in the context of the Hellenistic world, brought into existence by the conquests of Alexander the Great. In this melting pot of cultures, Hellenistic astrology emerged, enriched and transformed by Greek philosophical thought. Central to this transformation was the theory of the four classical elements—Fire, Earth, Air, and Water—posited by pre-Socratic philosophers as the fundamental constituents of all matter. These elements, deeply woven into Greek philosophy, would come to inform various fields, including astrology.

In this article, we will explore the significance of the four elements, their philosophical underpinnings, and their role in the astrological tradition by shedding light on the concept of “triplicities”.

By discussing these historical and philosophical foundations, I aim to offer insight into the cosmic forces that have captivated human imagination for centuries.

I. The Philosophical Significance of the Elements

The understanding of the four classical elements as the foundational principles of the cosmos has a rich philosophical history. This ancient concept laid the groundwork for both natural philosophy and astrological thought. It permeates the fabric of Western intellectual tradition and continues to resonate in various aspects of culture.

A) Empedocles and the introduction of the four-element theory:

Empedocles, a Pre-Socratic philosopher and poet hailing from Acragas in Sicily, emerged as a seminal figure in the 5th century BC. His doctrine of the four roots or elements—Fire, Earth, Air, and Water—laid the foundation for later natural philosophy, influencing both the scientific and mystical traditions.

In his poem “On Nature,” preserved through various fragments, Empedocles formulated the principle that all things are composed of these four eternal and unchangeable elements. He introduced a dynamic system where the elements combined and separated under the influence of two opposing forces: Love (Greek: Φιλότης), acting as the principle of attraction and union, and Strife (Greek: Νεῖκος), serving as the principle of repulsion and division.

Empedocles’ vision of the cosmos depicted a continuous cycle of formation and dissolution, governed by the interplay between Love and Strife. At one extreme, Love would entirely dominate, leading to a perfect blend of the elements, while at the other, Strife would separate them entirely, resulting in chaos. Human beings, animals, and the world’s features emerged from the mixing of these elements, and their combinations were held together or torn apart by these forces.

Furthermore, Empedocles introduced the concept of metempsychosis, or the transmigration of souls, arguing that souls, like elements, undergo cycles of rebirth and transformation.

Empedocles’ four-element theory had a lasting impact on later Greek philosophy, most notably in the works of Plato and Aristotle. Aristotle, in particular, integrated Empedocles’ ideas into his natural philosophy, adapting the elements to explain change in the physical world.

The elemental theory also permeated Medieval and Renaissance thought, influencing the alchemical tradition and shaping the understanding of the natural world in various cultural contexts, including Islamic philosophy.

Furthermore, the Empedoclean system provided a conceptual bridge to later astrological systems, including the understanding of triplicities in Western astrology, where the twelve zodiac signs are grouped into four sets of three signs each, aligned with the four classical elements.

B) Aristotle’s Addition of a Fifth Element, Aether or Quintessence:

Aristotle, the ancient Greek philosopher and student of Plato, made significant contributions to natural philosophy, ethics, logic, and many other fields. One of his most profound additions to the natural sciences was his introduction of a fifth element, known as Aether or Quintessence. This concept expanded upon the foundational work of Empedocles and marked a departure from the traditional four-element model.

In Aristotle’s cosmology, the four classical elements of Earth, Water, Air, and Fire formed the sublunary realm, where change, decay, and generation occurred. Beyond this realm, in the celestial spheres, Aether was the substance that comprised the stars, planets, and other heavenly bodies.

Unlike the earthly elements, Aether was considered to be eternal, immutable, and unchanging. Aristotle described it as a “divine” substance that transcended the natural decay and transformation associated with the sublunary world.

Aristotle’s concept of Aether was closely tied to his understanding of the celestial spheres. He posited that the heavens operated according to different principles than those governing the earthly realm. The heavenly spheres were perfect, eternal, and unchanging, moving in a perfect circular motion. The Aether was seen as the substance that enabled this motion, filling the void between the spheres and providing the medium for the fixed stars’ motion and the planets. The quintessential nature of Aether also reflected the spiritual and metaphysical dimensions of the universe, echoing the divine perfection associated with the heavens.

Aristotle’s addition of Aether as the fifth element had a lasting impact on both scientific and mystical traditions. In Medieval scholasticism, Aristotle’s cosmology became the dominant worldview, and the concept of Aether was adopted by scholars such as Thomas Aquinas.

During the Renaissance, the idea of Quintessence found a place in alchemical traditions, symbolising purity and the essence of perfection. It also influenced the development of early modern astronomy, before the Copernican revolution brought significant paradigm shifts. Furthermore, the concept of Aether continued to resonate in later scientific thought, particularly in the 19th-century physics’ search for the medium of light propagation, though this idea was eventually discarded with the advent of the theory of relativity.

C) Plato’s Geometrical Association of the Elements:

Plato’s influence on Western thought is vast, ranging from philosophy and mathematics to political theory. In his dialogue “Timaeus,” Plato introduced an innovative connection between the elements and geometry, associating the elements with specific regular polyhedra. This association was not merely symbolic; it was an integral part of his cosmological vision.

Plato’s geometric association of the elements is a prominent aspect of the “Timaeus” dialogue, where he describes the structure of the universe:

- Fire was associated with the tetrahedron, the simplest and sharpest of the shapes. This polyhedron consists of four faces, each an equilateral triangle. The sharpness of the tetrahedron symbolized the piercing nature of fire.

- Earth was symbolised by the hexahedron or cube, with six square faces. Its solidity and stability made it the natural symbol for earth.

- Air was connected with the octahedron, a shape with eight triangular faces. The octahedron’s relative complexity and lightness represented the nature of air.

- Water was linked to the icosahedron, a polyhedron with twenty triangular faces. Its multi-faced structure symbolised water’s fluidity and capacity to flow.

These geometric associations were not mere poetic devices; they carried deep philosophical implications. For Plato, the universe was a perfectly ordered and harmonious cosmos, and the association of elements with regular polyhedra reflected this order.

The geometric shapes also provided a logical structure for understanding how the elements could transform into one another. According to Plato, the elements were not immutable substances but rather could combine and transform through the geometric principles governing their shapes. This idea is rooted in the belief that the universe was created by a divine craftsman (Demiurge) who used eternal forms and mathematical principles to shape the material world.

Plato’s association of elements with geometric shapes influenced later philosophical and scientific thought. Medieval scholars and Renaissance thinkers continued to explore these connections, reflecting the timeless fascination with geometry and the natural world. The Platonic solids also became central to some esoteric and mystical traditions, symbolizing deeper spiritual truths. In modern times, the mathematical elegance of these shapes has inspired artists, architects, and even physicists.

While Plato’s association of elements with regular polyhedra is celebrated, it should be noted that the fifth Platonic solid, the dodecahedron, was not linked to any traditional element. Instead, Plato associated it with the entire cosmos or the “heavenly sphere,” hinting at a broader metaphysical dimension.

D) Stoic Philosophy and the Influence of the Elements on the Soul:

In the intellectual landscape of ancient Athens, the Stoic school of philosophy emerged as a force that coupled ethical living with a nuanced understanding of cosmology. Founded in the 3rd century BC, Stoicism, as articulated by its early proponents like Zeno, Cleanthes, and Chrysippus, navigated the terrains of both personal virtue and the broader structure of the universe. This discussion seeks to delve into how the Stoic cosmological view, deeply entwined with elemental theories, permeates the human soul and ethical conduct.

At the core of Stoic cosmology are two fundamental principles: the active principle known as the “Logos” or Reason, and the passive principle that manifests as matter or substance. Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, posited these dual principles as inseparable; the Logos serves as the animating, rational force within matter.

The Stoic philosophers divided matter into four primary elements: Fire, Air, Earth, and Water. These elements, far from being inert constituents of the universe, were deemed active players in the divine rationality that orchestrates the cosmos. According to Cleanthes, these elements are transformative and cyclical, reverting into one another in a cosmic dance that echoes the rational structure of the universe.

The Stoic concept that the human soul serves as a microcosm of the universe is a profound aspect of their teachings. Chrysippus, a pivotal figure in Stoic philosophy, introduced the term “pneuma,” or breath, to encapsulate the soul’s elemental nature. According to his writings, the pneuma is fundamentally a blend of Fire and Air. This mixture serves as the life-giving force and the foundation of rationality within humans, aligning each individual with the cosmic Logos. This pneumatic framework opens a door to a vitalistic understanding of the human soul. The individual is not merely a bystander in the universe but an active participant in a cosmos that is suffused with divine reason.

Within the ethical imperatives of Stoicism lies a focus on the cultivation of personal virtue. Chrysippus argues that this virtue is not an abstract ideal but a living practice of aligning one’s internal nature with the rational order of the universe. Because the Stoic soul is composed of elemental pneuma, achieving virtue inherently involves cultivating an elemental balance within oneself.

According to Seneca, a later Stoic philosopher, the soul’s alignment with the rational and elemental structure of the universe is the cornerstone of virtuous living. This equilibrium allows for a life in harmony not just with societal norms but with the cosmic order itself.

E) The Elements as Foundational Principles of Matter According to Ancient Philosophical Thought:

In the ancient philosophical tradition, the four-element theory played a critical role in shaping an understanding of the physical world. It was not merely an abstract cosmological concept but a foundational theory that penetrated various aspects of human life and thought. Here’s an expanded exploration of how the elements were seen as the basic principles of matter, influencing various fields from natural philosophy to ethics.

The four elements – Fire, Earth, Air, and Water – were seen as fundamental building blocks of the universe. They were considered eternal and unchangeable, underlying all physical phenomena.

- Fire: Represented transformation and was seen as the most volatile element.

- Earth: Symbolized solidity and stability, giving structure and form.

- Air: Denoted breath and life, acting as a mediator between fire and water.

- Water: Signified fluidity, connected with emotions and the unconscious.

These elements were understood to combine in various ways to create everything in the material world, from rocks and plants to animals and humans.

The concept of the four elements provided a framework for early scientific exploration. Ancient philosophers and physicians used this theory to explain various natural phenomena, such as weather patterns, geological formations, and biological processes. For example, the interaction of elements was used to describe the cycles of the seasons, where the heating of water (element of Water) by the Sun (element of Fire) would produce vapour (element of Air), leading to rainfall and nurturing the earth (element of Earth).

The theory also had a profound impact on medicine. Ancient Greek physicians like Hippocrates adopted the four-element theory to explain the human body’s constitution. They associated the elements with bodily humours:

- Fire: Yellow bile (Choler)

- Earth: Black bile (Melancholy)

- Air: Blood (Sanguine)

- Water: Phlegm

A balance of these humours was believed to result in good health, while an imbalance led to diseases. Medical treatments were designed to restore this elemental balance through diet, exercise, and other therapeutic practices. The four-element theory extended even to ethics and psychology. The elements were connected to different temperaments and personality traits, influencing human behaviour and moral choices. For instance, a person with a predominance of the “fire” element might be viewed as passionate and courageous but also prone to anger. Understanding these elemental influences was considered essential for personal development and ethical living.

{ For more details on the humours and temperaments in traditional astrology, check my article on the subject here. }

The concept of the elements provided a coherent and interconnected system that unified diverse phenomena. Everything in the cosmos was seen as interrelated, governed by the same principles. This belief laid the foundation for an integrated worldview that encompassed science, religion, ethics, and aesthetics.

II. The Elemental Associations in Astrology: Emergence of the Concept of Triplicities

The term “triplicities” represents one of the most profound aspects of Traditional Western Astrology. A triplicity refers to the grouping of the twelve zodiac signs into four sets of three signs each. These groups have been further associated with the four classical elements: Fire, Earth, Air, and Water. Understanding the coming into being of the triplicities requires a journey through various historical and philosophical layers, from ancient Babylonian to Hellenistic, Medieval, and Renaissance astrology.

A) The philosophical underpinnings:

The number three, or the Triad, holds significant importance in classical philosophy, symbolising harmony, balance, completion, and fulfilment. This belief permeates ancient traditions, from the Babylonians, who classified their gods into triads like Anu, Enlil, and Ea, to the Christian faith, with the concept of the Holy Trinity. The fascination with the number three also shaped the astrological concept of triplicities.

The emergence of triplicities began with the trigonal relationship of signs. The 1st-century astrologer Manilius described this relationship in his “Astronomica,” grouping the signs into four sets of triplicities.

“Where the circle of the zodiac’s rightward wheel is bounded, a line runs out into three equal lengths and joins itself at limits which are mutually extreme; the signs which the line strikes are called trigonal, because an angle is thrice formed and is assigned to three signs separated from each other by three intervening signs. The Ram beholds at equal distance the two signs of the Lion and the Archer rising on opposite sides of him; the signs of the Virgin and the Bull are in harmony with Capricorn …”

In the Hellenistic period, the understanding of triplicities evolved considerably, laying the foundation for the rich tapestry of astrological knowledge we have today. While Ptolemy, a towering figure in the fields of Greek astronomy and astrology, certainly played a crucial role in advancing various astrological theories through works such as “Tetrabiblos,” it was not he who explicitly tied the zodiac signs to the four elements—fire, earth, air, and water.

This particular development can be attributed to later Hellenistic astrologers including Valens, Firmicus, Hephaestio, Julian of Laodicea, and Rhetorius, who worked meticulously to associate each zodiac sign with a specific element. These attributions were more than mere classifications; they represented an intricate system that connected the zodiac signs in a web of relationships, painting a vivid picture of interconnected energies and temperaments based on the intrinsic qualities of the elements they were linked to. This system was grounded in the philosophy that the cosmos is a harmonious entity, with each component maintaining a symbiotic relationship with others.

Under this paradigm, the elements not only stood as symbols but were thought to influence the characteristics and destinies of individuals born under different signs. They represented a profound harmony, forged through the geometrical relationship symbolised by the trigon, a shape holding deep significance in ancient thought.

B) Ancient Assignment of Triplicity Rulers:

The doctrine of triplicity rulers in Traditional Western Astrology springs from a rich mosaic of symbolic interpretations, astronomical observations, and philosophical doctrines, with a central pillar being the intricate planetary joys doctrine. This foundational theory (which stems from the concept of the “Thema Mundi” or the birth chart of the Universe) is a testament to the deep-rooted harmonies within the universe, acting as a vibrant canvas where elemental correspondences, diurnal and nocturnal proclivities, and the singularities of planetary energies interweave to form a deeply coherent, yet complex system.

The planetary joys doctrine serves as an ancient cornerstone in astrological scholarship, providing a structured approach to understanding the cosmic orchestration of energies that guide human experiences and the natural world. Through this lens, each of the seven classical planets finds joy in a specific house, creating a set of relationships that echo through the triplicities and their corresponding rulers. The doctrine contemplates the nuanced dances of the celestial bodies, offering a map of strengths, dignities, and relationships that echo the foundational principles found in ancient philosophical texts and astronomical observations.

Delving deeper into the structured wisdom of astrological principles, the doctrine further allocates rulerships to each triplicity, a classification that comprises sets of three zodiac signs sharing common elemental backgrounds. The ruling planets for these triplicities are meticulously defined to govern day and night cycles individually, with some interpretations positing a third, participatory ruler, which holds sway over both periods, synthesising the energies and embodying the collective attributes.

This discerning arrangement, which is intrinsically tied to the cycles of day and night, strives to represent the dynamic interplay of energies in the cosmos, offering a harmonious blueprint that mirrors the universe’s structured chaos and the harmonious interplay of cosmic energies. It invites us into a celestial narrative, where each planet in its joy reflects a specific facet of human experience and the natural phenomena of our world, guiding us towards a profound comprehension of the cosmos’ rhythmic dance.

1°) Fire Triplicity: Aries, Leo, Sagittarius

Diurnal rulers: ☉ Sun, ♃ Jupiter, ♄ Saturn

Nocturnal rulers: ♃ Jupiter, ☉ Sun, ♄ Saturn

2°) Earth Triplicity: Taurus, Virgo, Capricorn

Diurnal rulers: ♀ Venus, ☽ Moon, ♂ Mars

Nocturnal rulers: ☽ Moon, ♀ Venus, ♄ Saturn

3°) Air Triplicity: Gemini, Libra, Aquarius

Diurnal rulers: ♄ Saturn, ☿ Mercury, ♃ Jupiter

Nocturnal rulers: ♃ Jupiter, ♄ Saturn, ☿ Mercury

4°) Water Triplicity: Cancer, Scorpio, Pisces

Diurnal rulers: ♀ Venus, ♂ Mars, ☽ Moon

Nocturnal rulers: ♂ Mars, ♀ Venus, ☽ Moon

Here is the summary table reflecting these distinctions:

| Triplicity | Signs | Diurnal Rulers | Nocturnal Rulers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fire (Aries) | ♈ Aries, ♌ Leo, ♐ Sagittarius | ☉ Sun, ♃ Jupiter, ♄ Saturn | ♃ Jupiter, ☉ Sun, ♄ Saturn |

| Earth (Capricorn) | ♉ Taurus, ♍ Virgo, ♑ Capricorn | ♀ Venus, ☽ Moon, ♂ Mars | ☽ Moon, ♀ Venus, ♄ Saturn |

| Air (Libra) | ♊ Gemini, ♎ Libra, ♒ Aquarius | ♄ Saturn, ☿ Mercury, ♃ Jupiter | ♃ Jupiter, ♄ Saturn, ☿ Mercury |

| Water (Cancer) | ♋ Cancer, ♏ Scorpio, ♓ Pisces | ♀ Venus, ♂ Mars, ☽ Moon | ♂ Mars, ♀ Venus, ☽ Moon |

This precise assignment of rulers resonates with the understanding of the elements and their respective qualities, diurnal or nocturnal alignments, and the intricate relationships between signs and planets. The ordering of these rulers underlines the complex interplay between the celestial bodies and the symphony of energies that they manifest.

C) Medieval and Renaissance Evolutions:

Islamic scholars like Al-Kindi preserved the concept of triplicities, but it was Al-Biruni who combined triplicities with Islamic cosmological views. Al-Biruni sought to align the abstract symbolism of triplicities with the concrete beliefs and ethical guidelines of Islam. For example, he might relate the element of Water with mercy and compassion, characteristics highly valued in Islamic teachings, or align the Fire element with divine justice and strength. By drawing parallels between the elements and Islamic virtues, Al-Biruni fostered a synthesis that made the concept of triplicities more accessible and acceptable within the Islamic world.

During the Renaissance, a revival in classical learning and the integration of Platonic, Neoplatonic, and Hermetic ideas profoundly impacted various intellectual domains, including astrology. Scholars like Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola were at the forefront of this intellectual movement, offering new perspectives on astrological concepts such as triplicities.

Ficino was particularly interested in the works of Plato and Neoplatonism, which delve into concepts of unity, duality, and the nature of the divine. In this context, he reinterpreted triplicities not merely as groupings of signs but as symbolic representations of deeper universal principles. By doing so, he offered an enriched framework where astrological symbols were seen as more than mere predictors of mundane events; they became keys to understanding deeper philosophical and metaphysical principles. The triplicities could be viewed as earthly mirrors of celestial archetypes, aligning with Platonic ideas that posit the material world as a reflection of a more perfect, immaterial realm.

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, another pivotal figure of the time, approached triplicities from a slightly different angle. His interest in reconciling different schools of thought led him to integrate astrological concepts with Christian theology through the lens of Hermeticism—a belief system that combines elements of astrology, theurgy, and philosophy. Mirandola emphasised the divine aspects of astrology, viewing triplicities as not just elemental groupings but as facets of a cosmic order that was inherently magical and divine. This was a bold stance, particularly during an era where the church had considerable influence, and it sought to situate astrology within the purview of divine creation and action.

Both scholars, in their unique ways, ushered in a new era of astrological thinking by bridging the gap between ancient wisdom and the evolving philosophies of the Renaissance. Their works signalled a shift from astrology being viewed solely as a tool for divination towards a more integrated discipline that could converse with philosophy, theology, and natural science. By reinterpreting triplicities in the light of Neoplatonic and Hermetic ideas, they enriched the tapestry of Renaissance thought and opened new avenues for the intellectual and spiritual application of astrology.

The development of the concept of triplicities in Traditional Western Astrology is a complex and fascinating journey. From its philosophical roots in the symbolism of the number three to its geometric representation as triangles within the zodiac, the concept evolved through various historical epochs. The intricate logic of triplicity rulers, tied to the diurnal and nocturnal qualities of planets, reflects a deep understanding of harmony and balance. Whether in the synthesis of Hellenistic thought or the preservation and innovation of Medieval and Renaissance scholars like Al-Biruni, Ficino, and Mirandola, the triplicities remain a profound and enduring aspect of astrological tradition.

III. Fire Signs and Ancient Philosophical Thought

Fire’s role in ancient cosmology is as radiant and transformative as the element itself. Serving as a symbol of change, vitality, and creation, Fire has captivated the imagination of philosophers since antiquity. The fire signs in astrology—Aries, Leo, and Sagittarius—evoke these elemental characteristics and align them with ancient wisdom, giving us insights into the interconnectedness of the universe and human existence.

Fire, in ancient philosophy, was far more than a mere physical substance. It was an element symbolizing transformation, change, and vitality. The continual dance of flames—never staying the same from one moment to the next—made Fire a symbol for the dynamism of life itself. Plato, in his “Timaeus,” associated Fire with the tetrahedron, the simplest of the Platonic solids, suggesting the most basic and transformative of the elements.

For Heraclitus, Fire was the foundational substance of the cosmos. It epitomized constant change and transformation. In a famous fragment, Heraclitus stated, “Everything flows, and nothing stays” (Heraclitus, Fragments, DK B30). In this worldview, Fire was not just a constituent element among others but the very essence of change and the dynamism of existence.

Aries, Leo, and Sagittarius each bring their unique attributes to the astrological tableau of Fire signs:

- Aries: Ruled by Mars, Aries embodies the aggressive and pioneering spirit of Fire. In the “Anthology,” Valens describes Aries as “masculine” and “fiery”, mirroring the ancient understanding of Fire as an initiator of change and a force of vital energy.

- Leo: Governed by the Sun, Leo resonates with the life-giving and illuminating aspects of Fire. This association is consistent with Plato’s identification of the Sun as the “child of goodness,” disseminating light and life (Plato, “Republic,” Book VI).

- Sagittarius: With Jupiter as its ruling planet, Sagittarius reflects Fire’s expansive and philosophical nature. The largeness of Jupiter, both in physical size and in its mythological symbolism of wisdom and justice, is echoed in Sagittarius’ quest for truth and meaning (Ptolemy, “Tetrabiblos,” Book I, Chap. 12).

The Fire signs—Aries, Leo, and Sagittarius—act as living, breathing embodiments of ancient philosophical concepts about Fire. They epitomise creative energy, enthusiasm, and the desire for transformation. As Plato suggested in his cosmological work, there exists an intricate correspondence between the world’s soul and its visible manifestations. This worldview, foundational to ancient thought, sees each individual as a microcosm reflecting the larger cosmic macrocosm.

IV. Earth Signs and Ancient Philosophical Perspectives

The concept of Earth as an element has resonated through various philosophical paradigms, especially in the ancient world. This section aims to explore Earth as an element of stability, form, and materiality, as well as its embodiment in the zodiac Earth signs: Taurus, Virgo, and Capricorn. As we journey through the intertwined narratives of ancient philosophy and astrology, it becomes evident that the concept of Earth has always been a cornerstone for understanding the world in a foundational way.

In ancient Greek philosophy, Earth was often considered the element that provides stability and form. Empedocles, a pre-Socratic philosopher, included Earth in his theory of the four elements as the manifestation of material solidity and resistance. Plato, in his work “Timaeus,” associated Earth with the hexahedron, emphasising its geometric stability and form. Earth was seen as the receptacle of forms, a canvas upon which the other elements—Air, Fire, and Water—could interact and manifest.

Democritus, an ancient philosopher best known for his theory of atomism, further highlighted Earth’s solidity. According to Democritus, all matter was composed of indivisible atoms moving in the void, and it was their arrangement and shape that determined the characteristics of each element. In his writings, Earth’s atoms were considered to be particularly irregular, making them more likely to interlock and hence giving Earth its solid, stable nature. Democritus’ atomism provides a valuable framework for understanding Earth as the epitome of materiality and solidity in the ancient elemental scheme.

Astrology, an ancient system that evolved alongside philosophical traditions, assigns Taurus, Virgo, and Capricorn to the Earth element. Taurus, ruled by Venus, aligns with Earth’s association with materiality and form, often exemplifying a love for luxury and sensory experiences. Virgo, under Mercury’s rulership, reflects Earth’s practical, analytical, and organising attributes, correlating with Plato’s emphasis on form and geometric stability. Finally, Capricorn, ruled by Saturn, embodies the aspect of Earth concerned with structure, discipline, and longevity, attributes that can be traced back to the elemental understandings of both Empedocles and Plato.

The Earth signs—Taurus, Virgo, and Capricorn—are often seen as the epitomes of solidity, pragmatism, and material presence. This astrological perspective aligns well with ancient philosophical thought, which viewed Earth as the bedrock element providing stability and form to the universe. Whether it is the aesthetic appreciation of Taurus, the methodical nature of Virgo, or the disciplined structure of Capricorn, each sign reflects different facets of the Earth element as understood by philosophers like Empedocles, Plato, and Democritus.

V. Air Signs in Ancient Philosophical Texts

The concept of Air as an elemental force has a long and significant history in the annals of ancient philosophy. It has often been associated with ideas of movement, intellect, and the ethereal. This section delves into the complex relationship between the element of Air and its manifestations in the zodiac signs Gemini, Libra, and Aquarius, through the lens of ancient philosophy.

In ancient philosophical texts, Air has often been represented as an active, vital force. Unlike Earth, which symbolises stability and materiality, Air is the element of change, imbued with qualities of intellect and movement. Empedocles listed Air among the four root elements and associated it with the fundamental qualities of wetness and heat. Furthermore, Plato, in his dialogue “Timaeus,” linked Air to the octahedron, emphasising its less stable but highly dynamic nature.

Among the Pre-Socratics, Anaximenes of Miletus gave Air a particularly special status. In his cosmological model, Air was considered the “arche,” or the principle from which everything else emanated. Anaximenes posited that the entire cosmos was composed of different states of Air, condensed or rarefied to varying degrees. Through processes of condensation and rarefaction, Air transformed into other elements and substances, making it the most foundational element in Anaximenes’ worldview.

From an astrological perspective, the zodiac signs associated with the element of Air are Gemini, Libra, and Aquarius. Gemini, ruled by Mercury, embodies the mercurial, communicative aspects of Air, which find a parallel in Anaximenes’ view of Air as the source of all movement and change. Libra, ruled by Venus, leans towards the intellectual and ethical dimensions of Air, corresponding to Plato’s focus on geometry and form as abstract qualities. Lastly, Aquarius, ruled by Saturn in traditional astrology, aligns with Air’s foundational, all-encompassing nature, much like how Anaximenes considered Air as the primal principle of the cosmos.

In the broad tapestry of astrological symbols and ancient wisdom, Air signs stand as exemplifications of intellect, communication, and abstraction. Their attributes are not mere coincidental alignments but rather an extension of the foundational philosophies laid down by figures like Empedocles, Plato, and Anaximenes. Each sign—Gemini with its adaptability, Libra with its intellect, and Aquarius with its universality—reflects different facets of the Air element, fulfilling ancient philosophical postulates in a vivid and immediate way.

VI. Water Signs and Ancient Philosophical Interpretations

Water, an element that has long captured the imaginations of philosophers and astrologers alike, is often associated with fluidity, emotion, and intuition. This section delves into the intellectual heritage surrounding the element of water, focusing on its significance in ancient philosophy and its corresponding implications for the astrological water signs: Cancer, Scorpio, and Pisces.

Ancient philosophy has bequeathed us profound insights into the nature of water as an elemental force. For example, in Plato’s “Timaeus,” water is associated with the icosahedron, a geometric shape symbolising its fluid, transformative quality. Unlike Earth, which epitomises stability and form, or Air, which represents intellect and movement, water is linked with qualities of emotion and intuition. It serves as the natural element governing relationships, as well as the depth of the unconscious mind.

Among the Pre-Socratic philosophers, Thales of Miletus holds a pivotal place for positing water as the “arche,” or the primal substance, from which all things emanate. Thales argued that water is the most adaptive and vital element, capable of becoming vapour or ice, and thus the most plausible candidate for the source of all life and matter. His idea deeply influenced subsequent generations of philosophers and laid the groundwork for later theories about the primordial substance of the cosmos.

In astrology, the water signs—Cancer, Scorpio, and Pisces—are ruled by the Moon, Mars, and Jupiter, respectively. Each of these signs embodies characteristics closely aligned with the ancient philosophical understandings of water. Cancer, governed by the Moon, correlates with the nurturing, cyclical aspects of water, reflecting Thales’ notion of water as the source of life. Scorpio, ruled by Mars, embodies water’s transformative and intense nature, resonating with Plato’s association of water with the depths of the unconscious. Pisces, under the jurisdiction of Jupiter, reflects water’s adaptability and spiritual depth, capturing the essence of water as a vital, ever-changing element.

The astrological water signs are not merely symbols but living exemplifications of ancient philosophical ideas. Cancer, with its nurturing essence, Scorpio, with its transformative power, and Pisces, with its spiritual depth, each reflect different facets of the rich intellectual heritage surrounding the element of water. They epitomize emotion, intuition, and adaptability, serving as gateways to understanding the multidimensional qualities that water has been philosophically attributed.

The elemental theories in astrology offer more than symbolic categorizations or personality indicators; they are, at their core, philosophical constructs rooted in ancient wisdom. As we traverse this celestial landscape—marked by Fire, Earth, Air, and Water—we are following the intellectual pathways laid by the great thinkers of antiquity.

From Empedocles’ pioneering theory of the four elements to Aristotle’s introduction of a fifth, the Quintessence, ancient philosophers have bestowed upon us a rich cosmological inheritance. Plato’s geometric associations of the elements and Heraclitus’ principle of eternal change remind us that these elemental theories were conceived not as mere categories, but as profound metaphysical insights into the nature of existence. Such foundations have deeply influenced the structure and symbolism in astrology, offering a complex interplay between the individual and the cosmos.

The teachings of ancient philosophers continue to echo in the vaults of modern astrological thought. Whether it’s the Stoic philosophy of elemental balance within the soul or the influence of celestial bodies as described by Claudius Ptolemy in his “Tetrabiblos,” the ancient underpinnings are impossible to ignore (Stoic Texts, Epictetus, “Discourses,” Book III; Ptolemy, “Tetrabiblos,” Book I, Chap. 2).

Astrology, in many ways, serves as a bridge between the philosophical insights of the past and contemporary spiritual and psychological inquiries. The journey through the celestial and elemental realms of astrology is not a mere escapade but a venture into a cosmos deeply imbued with philosophical meaning. As we delve deeper into the traits of our sun signs or ponder the influence of our ruling planets, let us not forget the ancient wisdom that serves as the bedrock of these beliefs. Aristotle once said that “the unexamined life is not worth living” (“Nicomachean Ethics,” Book I). As seekers on this astrological journey, it is not just beneficial but essential to engage with the philosophical principles that have shaped this cosmic language.

As we navigate the complexities of our lives through the lens of astrology, we have much to gain from revisiting the foundational philosophies that have sculpted this ancient practice. Through a deeper understanding of these roots, we enrich not just our astrological literacy but also our broader quest for knowledge and meaning. The elements may serve as the alphabet, but it is philosophy that constructs the sentences, telling the intricate story of our existence within the cosmic tapestry.

Thank you for reading.

Fuel my caffeine addiction and spark my productivity by clicking that ‘Buy me a coffee’ button—because nothing says ‘I love this blog’ like a hot cup of java!

Buy Me a Coffee

Your Astrologer – Theodora NightFall ~

Your next 4 steps (they’re all essential but non-cumulative):

Follow me on Facebook & Instagram!

Subscribe to my free newsletter, “NightFall Insiders”, the place where the most potent magicK happens, and get my daily & weekly horoscopes, exclusive articles, updates, and special offers delivered directly to your inbox!

Purchase one of my super concise & accurate mini-readings that will answer your most pressing Astro questions within 5 days max!

Book a LIVE Astro consultation with me!