No products in the basket.

Harmony of Humours & Temperaments: One of the Backbones of Traditional Astrology

Dear NightFall Astrology readers,

Embarking on the journey into traditional astrology, we are greeted by a tapestry of intricate philosophies and intertwined theories. In the heart of this maze, standing prominent and undeterred by the sands of time, lie the doctrines of the Four Humours and the Temperaments. These doctrines, often considered the cornerstones of traditional astrology, play a crucial role in the art of astrological interpretations.

A deep dive into the annals of ancient wisdom reveals that the roots of these theories are firmly planted in the fertile soil of ancient Greek intellect. It was here that the luminary figures of Hippocrates, Aristotle and Galen set forth principles that would permeate not only the medical field but also extend to the realm of astrology. They proposed theories that would eventually become a lens through which one could scrutinise and comprehend an individual’s physical and mental wellness, inherent personality traits, and even perceived destinies.

The doctrine of the Four Humours, in essence, is a holistic understanding of human health, where equilibrium between different bodily fluids (black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood) is deemed to be the keystone of well-being. On the other hand, the Doctrine of Temperaments provides a unique perspective of individual dispositions, classifying them into four distinct categories – sanguine, choleric, melancholic, and phlegmatic.

In this exploration, we’ll delve deeper into these doctrines, unravel their mysteries, and elucidate their influence on traditional astrology. We’ll journey back to the cradle of Western civilisation, to ancient Greece, and trace the evolution of these concepts from their inception to their eventual incorporation into the fascinating world of astrology.

I. The Four Humours: An Examination of Ancient Greek Influence

A critical juncture in the annals of medicine and philosophy was the inception and development of the theory of the Four Humours.

The humours – black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood – were perceived as pivotal components orchestrating our physical conditions and emotional states. This intricate tapestry of bodily substances weaves through the history of medicine and philosophy, carrying with it a vast treasure trove of wisdom and understanding.

The roots of this concept can be traced back to the time of the pre-Socratic philosophers. Among them, most notably was Empedocles, a politician and religious teacher from Acragas, Sicily, who introduced the theory of the four elements – fire, air, earth, and water, referred to as “roots” in the 5th century BC. He established a medical school, and his theories influenced key figures like Plato, Aristotle, and Hippocrates.

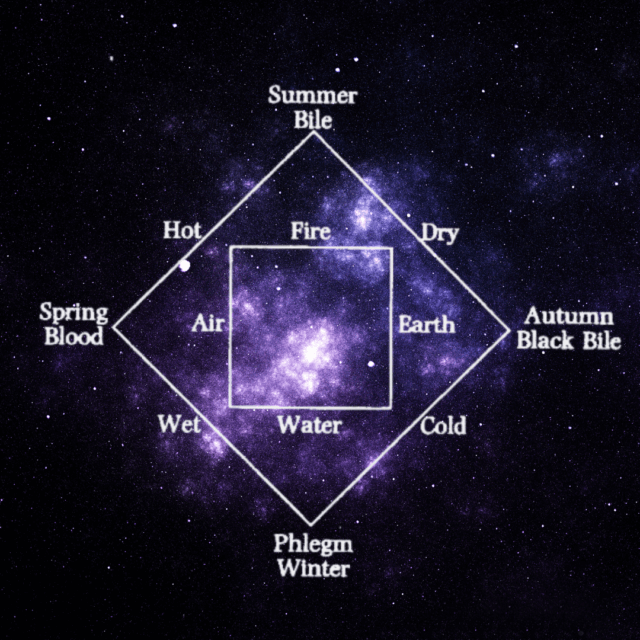

His belief that Love and Strife were forces binding and separating these roots laid the groundwork for the medical application of these elements. This theory, suggesting that each root was irreducible and equivalent in strength, was tied to the concepts of hot, cold, wet, and dry, providing a basis for more intricate theories by Aristotle.

Following Empedocles, Hippocrates developed the system of humours leading to temperament theory. He extended Empedocles’s concepts to human physiology, correlating the components of the macrocosm (world) to the microcosm (body), an idea later adopted by astrologers in temperament theory.

Hippocrates associated fire, earth, air, and water with the body’s four humours: yellow bile, black bile, blood, and phlegm. Moreover, he linked these humours with the seasons, thereby connecting the physiological changes in the body with seasonal variations (see the image below). Following Pythagoras and Alcmaeon’s philosophies of balance, Hippocrates argued that health was the result of maintaining a balance of these four humours.

While he initially only discussed physical symptoms related to the humours, Hippocrates began to associate them with aspects of the soul, paving the way for later thinkers to fully apply these qualities to psychological characteristics. Despite the difficult writing style, his treatise, “Humours”, provides crucial insight into humoural theory.

Moving on later in time, born in 384 BC, Aristotle, a pupil of Plato and tutor to Alexander the Great, significantly impacted Western philosophy and science. His extensive body of work included exploring elements and qualities, a perspective later adopted by thinkers like Ptolemy and Galen.

Aristotle’s treatise, “On Coming-to-be and Passing-away”, begins with Empedocles’ theory of eternal elements. Aristotle, however, adds a mechanism to this, suggesting elements “come to be” and “pass away” due to their inherent qualities.

Aristotle proposed that each element consists of two contrasting qualities: hot-cold and wet-dry. These contraries cannot coexist in one element; hence, four possible pairs result—hot-wet, hot-dry, cold-wet, cold-dry—each corresponding to an element: Fire (hot-dry), Air (hot-wet), Water (cold-wet), and Earth (cold-dry).

Aristotle then elucidates the transformation of elements into each other. Elements with a common quality can convert more readily, e.g., air (hot-wet) becomes fire (hot-dry) as moisture decreases, and fire turns into earth (cold-dry) when heat reduces. This cyclical transformation is simpler since only one quality needs to change. In contrast, elements without a common quality require a more complex, two-stage transition, e.g., fire can become water via an intermediate step involving air or earth. Despite the complexity, this process is still cyclical.

The Greeks significantly shaped Roman culture in various domains, including philosophy, literature, art, science, and medicine, and it was with Galen of Pergamon (c. 129-200 AD), a renowned Greek surgeon, physician, and philosopher that the doctrine of the four humours really cristallised. Around 162 AD, he founded a flourishing practice in Rome, becoming Emperor Marcus Aurelius’s personal physician. In his extensive writings, Galen advocated for a rational, philosophical approach to medicine. He believed physicians should follow in Hippocrates’s footsteps, valuing logic and temperance over wealth.

Thus, blood with heat and moisture (akin to air), yellow bile with heat and dryness (like fire), black bile with coldness and dryness (similar to earth), and phlegm with coldness and moisture (comparable to water). The theory suggested that a balance among these humours was crucial for maintaining health, while an imbalance could result in disease.

Galen expanded upon this existing framework by connecting the humours to different bodily organs and functions. He believed blood was produced in the liver, yellow bile in the gallbladder, black bile in the spleen, and phlegm in the lungs and brain. He also associated each humour with specific temperaments: sanguine (blood), choleric (yellow bile), melancholic (black bile), and phlegmatic (phlegm).

Galen further argued that an individual’s temperament could be determined by the predominant humour in their body, and this, in turn, could influence their health and personality traits…

II. The Doctrine of Temperament in Traditional Astrology

(i) First things first: What is temperament?

Defining temperament calls for a nuanced understanding of what it doesn’t represent. In contrast to personality, which is moulded by both internal predispositions and external influences, temperament is exclusively innate. It’s also distinct from character, which carries an undertone of moral judgement in contemporary English language. Originating from the Greek word ‘charakter,’ denoting a ‘stamp’ or ‘impression,’ character suggests an external imprint on an individual, unlike temperament, which springs from within.

Temperament, on the other hand, is a fundamental aspect of our individuality that we are born with and retain throughout our lives. This can be easily observed in families with multiple children, where differing temperaments manifest from birth and become more pronounced with age.

Tracing the etymology of the term ‘temperament’ leads us to the Latin ‘temperamentum,’ which translates to ‘mixture.’ But what is being mixed? According to ancient Greek theorists, temperament results from the blend of different qualities, elements in physics, and humours in medicine, which takes us back to the Doctrine of Temperament being initially based on The Four Humours.

The Greeks pursued an equilibrium or balance among these elements and humours, terming a well-balanced individual as ‘well-tempered.’ This notion of ‘good temper’ has survived into modern English. Identifying a person’s temperament became crucial to addressing imbalances.

(ii) What is the Doctrine of Temperament?

As mentioned earlier, Aristotle, an emblematic figure of Classical Greek philosophy, planted the earliest seeds of the Doctrine in the 4th century BC. He introduced the concept of primary qualities — hot, cold, dry, and moist — and associated these with the four classical elements — fire, air, water, and earth. He posited that pairs of these qualities intermingle to birth the four temperaments, forming a cornerstone of the Doctrine. This theory was later further developed by Galen.

The temperaments — sanguine, choleric, melancholic, and phlegmatic — each embody a distinct amalgam of qualities and elemental characteristics, providing a foundational framework for character assessment.

Further refining this framework, Claudius Ptolemy, an eminent 2nd-century polymath, added the celestial dimension. His work “Tetrabiblos” remains a seminal text in astrology, where he meticulously assigned specific qualities to astrological signs and planets, intricately connecting them to the temperaments. Other Ancient astrologers — such as Manilius, Vettius Valens, Antiochus of Athens, Paulus Alexandrinus, and Rhetorius — have contributed to the elaboration of this Doctrine through their work on the triplicities (elements) and quadruplicities (modalities) of the zodiac signs.

Thus, temperaments were derived from the predominating planetary influences and inherent qualities evident at the moment of birth. This celestial alignment had the power to characterise a person’s fundamental nature as predominantly choleric (hot and dry), melancholic (cold and dry), sanguine (hot and moist), or phlegmatic (cold and moist).

Mirroring the Four Humours, each temperament is associated with specific astrological elements and signs:

The choleric temperament, distinguished by its dynamic energy, passion, and determination, aligns with the fire (active) signs: Aries, Leo, and Sagittarius. The sanguine temperament, displaying sociability, creativity, and intellectual curiosity, corresponds to the air (active) signs: Gemini, Libra, and Aquarius.

The melancholic temperament, marked by focused thought, contemplation, and a tendency towards introspection, resonates with the earth (passive) signs: Taurus, Virgo, and Capricorn.

Lastly, the phlegmatic temperament, with its calm demeanour, supportive nature, and intuitive inclinations, is in harmony with the water (passive) signs: Cancer, Scorpio, and Pisces.

The ancient Greek philosophy of a cosmic-human connection deeply influences traditional astrology through concepts like the Four Humours and the Doctrine of Temperaments. These theories create a vibrant astrological discourse, grounding astrology in Greek cosmological and medical thought. This connection between Greek philosophical heritage and modern astrology enhances astrological chart interpretation and remains relevant today.

Thank you for reading.

Fuel my caffeine addiction and spark my productivity by clicking that ‘Buy me a coffee’ button—because nothing says ‘I love this blog’ like a hot cup of java!

Buy Me a Coffee

Your Astrologer – Theodora NightFall ~

Your next 4 steps (they’re all essential but non-cumulative):

Follow me on Facebook & Instagram!

Subscribe to my free newsletter, “NightFall Insiders”, the place where the most potent magicK happens, and get my daily & weekly horoscopes, exclusive articles, updates, and special offers delivered directly to your inbox!

Purchase one of my super concise & accurate mini-readings that will answer your most pressing Astro questions within 5 days max!

Book a LIVE Astro consultation with me!