No products in the basket.

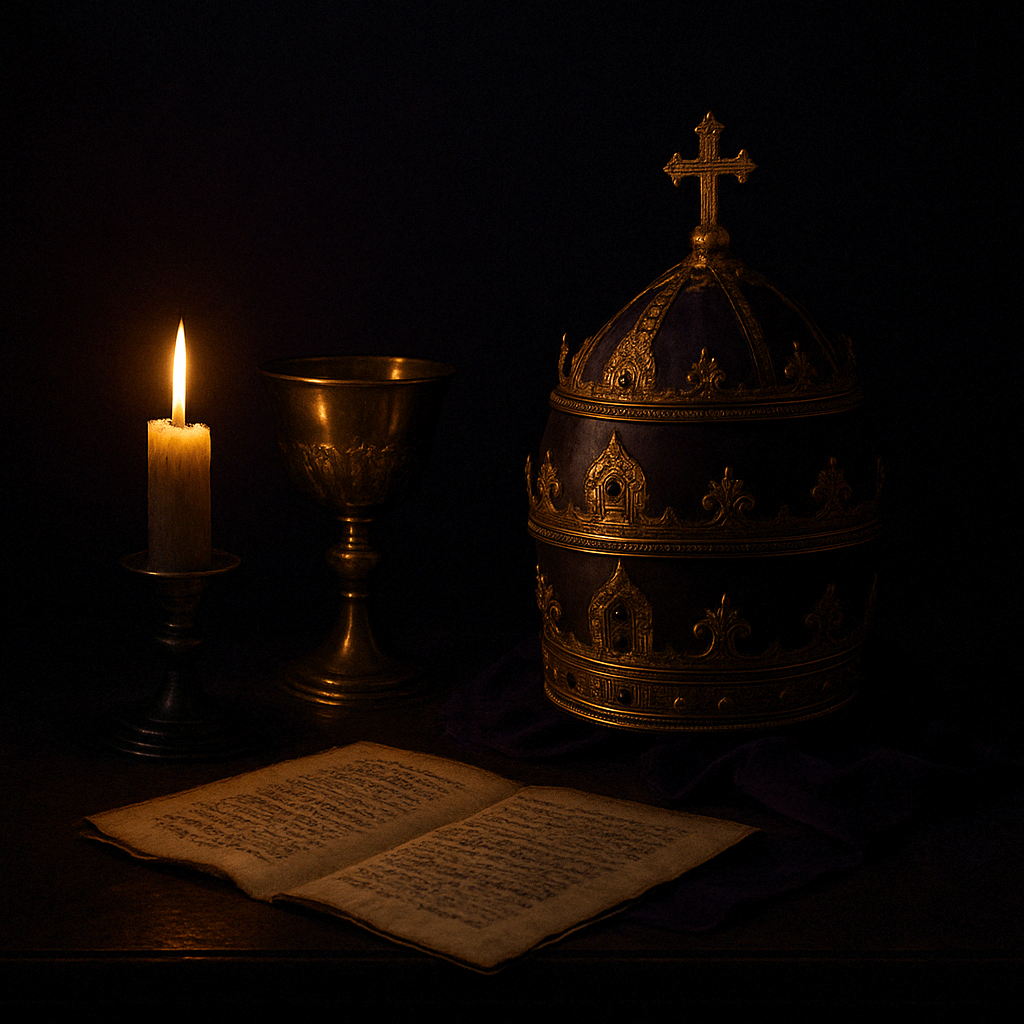

From the Stars to the Cross: The Transformation of Firmicus Maternus in Constantine’s Empire

Dear NightFall Astrology readers,

Firmicus Maternus stands out as a significant figure in early 4th-century Rome, transitioning from a renowned Roman astrologer to a fervent Christian apologist. His journey from authoring “Mathesis,” an authoritative astrological work, to critiquing pagan religions in “De errore profanarum religionum” (The Error of the Pagan Religions), mirrors the Roman Empire’s shift under Emperor Constantine I from polytheism to Christianity. This era, marked by Constantine’s conversion and the promotion of Christianity, saw profound changes in Rome’s religious and socio-political landscape. Firmicus’s life and works embody the complex interplay of religion, astrology, and politics during this transformative period.

This article explores Firmicus’s transition, highlighting how his experiences reflect the broader cultural and religious evolution of the Roman Empire from the stars to the cross.

I. Firmicus’ Early Life & Career as an Astrologer:

Firmicus Maternus, a figure of considerable renown in the annals of ancient astrology, embarked on his distinguished journey in the early 4th century AD, amidst the backdrop of profound religious and cultural shifts within the Roman Empire. Originating from a family of senatorial rank, Firmicus enjoyed the privileges associated with his class, receiving a comprehensive education rooted in Greco-Roman intellectual traditions. Before his foray into astrology, Firmicus initially pursued a career as an advocate, where his rhetorical prowess and aristocratic training were directed towards combating dishonesty, greed, and the mistreatment of the less fortunate. However, his dedication to integrity led to animosity rather than acclaim, prompting him to abandon the legal profession in disgust. Disenchanted with the venality he encountered, Firmicus sought solace in the study of the stars, turning away from the earthly transgressions of his peers to engage in the lofty pursuits of astrology (Johannes Quasten, Walter J. Burghardt, and Thomas Comerford Lawlor, eds. “Firmicus Maternus: The Error of the Pagan Religions”, Issue 37 (1970)).

This transition was not merely a personal inclination but reflected the era’s widespread fascination with astrological practices. Firmicus’s astrological studies, informed by a rigorous educational regimen from the era’s leading scholars, encompassed philosophy, rhetoric, and the quadrivium. This diverse intellectual background provided him with a robust foundation to explore astrology, aligning him with the scholarly pursuits of his time and marking the beginning of his significant contributions to the astrological canon. Through this journey, Firmicus Maternus emerged as a pivotal figure, bridging the gap between the classical intellectual traditions of his upbringing and the burgeoning field of astrology that captivated the Roman world

Around 334–337 AD, Firmicus authored his magnum opus, the Mathesis, dedicating this seminal work to Lollianus Mavortius, the governor of Campania. Mavortius, known for his astute knowledge of astrology, not only inspired Firmicus but also provided encouragement throughout the composition of this comprehensive handbook. The Mathesis, comprising eight books, stands as the most extensive Latin astrological treatise to have survived to this day. Its scope spans the fundamentals of astrology, including detailed analyses of the zodiac, planets, and houses, alongside discussions on natal astrology, catarchic astrology (electional astrology), and interrogations (horary astrology). In crafting the Mathesis, Firmicus integrated knowledge from Greek, Egyptian, and Babylonian traditions, preserving a vast corpus of astrological lore (Holden, James H., “A History of Horoscopic Astrology,” American Federation of Astrologers, 1996).

The Mathesis is among the last comprehensive handbooks of “scientific” astrology that circulated in the West prior to the advent of Arabic texts in the 12th century. This work not only reflects the intellectual zeitgeist of Firmicus’s time, particularly under Constantine I’s reign, but also serves as a pivotal link in the transmission of astrological knowledge. Despite Constantine’s initial policies of religious pluralism, the ascent of Christianity increasingly marginalised pagan practices, including astrology. Yet, Firmicus, through the Mathesis, sought to articulate astrology as a divine science compatible with Christian doctrine, arguing for its validity as a means of divining the divine order (Clark, Gillian, “Christianity and Roman Society,” Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Notably, Augustine of Hippo, who was drawn to astrology in his youth during the mid-fourth century, later vehemently opposed the study for its impieties, particularly criticising the astrological assertion of the planets as divinities, and on rational grounds, such as the divergent destinies of twins. Despite such critiques, the Mathesis persisted as a cornerstone of astrological study, first printed by Aldus Manutius in 1499 and frequently reprinted thereafter.

Firmicus’s Mathesis not only mirrored the astrological thought of his era but also significantly shaped it. By democratizing access to astrological knowledge, Firmicus bridged the gap between pagan and Christian intellectual traditions, illustrating the nuanced interplay of religion, science, and philosophy during a time of profound societal change (Salzman, Michele Renee, “The Making of a Christian Aristocracy: Social and Religious Change in the Western Roman Empire,” Harvard University Press, 2002).

In essence, Firmicus Maternus’s early forays into astrology, culminating in the creation of the Mathesis, underscore the dynamic intellectual and cultural currents of his time. His contributions not only safeguarded the wisdom of ancient astrology but also engaged with the evolving religious milieu of the Roman Empire, offering a lasting legacy that continues to inspire and challenge scholars today.

II. The Reign of Constantine I & its Impact on Astrology:

The reign of Constantine I (306-337 AD) marks a pivotal period in the history of the Roman Empire, characterised by significant transformations in the religious and cultural landscape. Central to this transformation was Constantine’s conversion to Christianity, an event that not only reshaped his personal life but also had far-reaching effects on the empire’s religious and socio-political fabric. This essay explores Constantine’s conversion and its profound impacts on the status of astrology and religion, examining his policies towards pagan practices and their practitioners, and delineating the shifting place of astrology in this transforming society.

Constantine’s conversion to Christianity is often attributed to a vision he experienced before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 AD, where he reportedly saw a cross in the sky accompanied by the words “In this sign, conquer” (Lactantius, “On the Deaths of the Persecutors”, 318 AD; Eusebius, “The Life of Constantine”, circa 337 AD). This divine encounter prompted Constantine to embrace Christianity, fundamentally altering the religious orientation of his reign and the empire at large. The issuance of the Edict of Milan in 313 AD, which proclaimed religious tolerance across the empire, marked a significant departure from previous policies of Christian persecution. Constantine’s conversion and subsequent support for Christianity facilitated its growth and institutionalization, ultimately leading to its status as the dominant religion of the Roman Empire (Barnes, T.D., “Constantine: Dynasty, Religion and Power in the Later Roman Empire”, Wiley-Blackwell, 2011).

Astrology, deeply embedded in Roman culture and society, faced a new set of challenges in the wake of Constantine’s conversion. Prior to Constantine’s reign, astrology was widely practised and accepted across various strata of Roman society, from the imperial court to the common populace. Astrologers often held significant sway, advising emperors and military leaders on auspicious dates for battles and political events (Cramer, Frederick H., “Astrology in Roman Law and Politics”, American Philosophical Society, 1954). However, the ascent of Christianity brought with it a doctrinal aversion to astrology, which was seen as incompatible with Christian teachings on divine providence and human agency.

Constantine’s approach to pagan practices, including astrology, was initially one of tolerance, reflecting his broader policy of religious inclusivity. However, as his reign progressed and his commitment to Christianity deepened, Constantine began to implement measures that subtly undermined pagan religions and practices. While he did not outright ban astrology, his patronage of Christianity and construction of Christian churches symbolised a significant shift in imperial favour away from paganism (Drake, H.A., “Constantine and the Bishops: The Politics of Intolerance”, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000).

Moreover, Constantine’s laws increasingly reflected Christian ethics and morality, indirectly impacting practices associated with astrology and divination. For example, his legislation against magic and divination can be interpreted as indirectly targeting astrological practices, which were often conflated with other forms of pagan divination (MacMullen, Ramsay, “Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries”, Yale University Press, 1997). Despite these measures, astrology continued to be practised, albeit with greater discretion and, in some cases, by integrating itself with Christian cosmology to survive in a changing religious landscape.

The reign of Constantine I and his conversion to Christianity marked a turning point in the history of the Roman Empire, heralding significant changes in the religious and cultural fabric of society. These transformations had profound implications for the practice and acceptance of astrology, a discipline that was deeply entrenched in Roman life. While Constantine’s policies towards pagan practices, including astrology, were not overtly hostile, the privileging of Christianity and the gradual institutionalisation of Christian beliefs inevitably led to a diminished role for astrology within the empire. The shift in imperial favour from paganism to Christianity, coupled with the Christian critique of astrology, contributed to the reconfiguration of the empire’s religious landscape, setting the stage for the further marginalisation of astrology in the centuries to come. Thus, the influence of Constantine’s reign on astrology and religion reflects the complex interplay between personal belief, political power, and cultural transformation in the late Roman Empire.

III. Firmicus Maternus’ Conversion to Christianity:

Julius Firmicus Maternus, a notable figure in the 4th century, initially gained recognition for his contributions to astrology, authoring the comprehensive treatise “Matheseos Libri VIII.” However, his later life marked a significant pivot as he embraced Christianity, a transformation that culminated in the writing of “De errore profanarum religionum” (The Error of the Pagan Religions). Firmicus’s conversion is not merely a personal anecdote but reflects the complex interplay of personal conviction, philosophical inquiry, and the socio-political milieu of the Roman Empire undergoing significant religious transformation.

The exact motives behind Firmicus’s conversion remain partly speculative, given the scarcity of autobiographical details. However, scholars suggest that his astrological studies, which delved into the mysteries of the cosmos, may have paradoxically led him to question the deterministic framework of astrology, paving the way for a Christian worldview that emphasised divine providence and free will (Clark, Gillian, “Christianity and Roman Society”, Cambridge University Press, 2004). This intellectual transition signifies a deep philosophical reorientation, from a pagan cosmology to a Christian understanding of the universe’s moral and spiritual order.

Firmicus’s conversion also occurred within a broader socio-political context marked by Constantine the Great’s endorsement of Christianity, which significantly altered the religious landscape of the Roman Empire. The conversion of such a prominent figure can be seen as emblematic of the period’s shifting allegiances, from traditional pagan beliefs to a burgeoning Christian orthodoxy that increasingly dominated the empire’s cultural and political institutions (Cameron, Averil, “The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity”, Routledge, 1993). This backdrop likely provided both the impetus and the support necessary for Firmicus to openly embrace and advocate for his new faith.

“De errore profanarum religionum” stands as a vehement critique of pagan religions, articulating Firmicus’s disdain for the practices and beliefs he once might have adhered to or at least coexisted with. This work is not only a reflection of his personal conversion but also serves as a broader indictment of paganism from the perspective of Christian orthodoxy.

In “De errore,” Julius Firmicus Maternus constructs a comprehensive and meticulous argument against the foundations and practices of pagan religions, utilising an impressive array of rhetorical devices and strategies to make his case. The treatise is structured to systematically dismantle the credibility and moral standing of pagan rituals and deities, which Firmicus posits as antithetical to the truths and salvation offered by Christianity.

Firmicus’s rhetorical approach in “De errore” is multifaceted, blending logical argumentation, moral persuasion, and emotive appeal to engage and convince his readers. He meticulously catalogues various pagan practices, from the worship of traditional Roman deities to the more esoteric rites of the Eastern mystery religions, critiquing them for their reliance on what he perceives as superstition and magic. By providing detailed descriptions of these practices, Firmicus aims to expose their supposed absurdity and moral bankruptcy to his audience.

A significant portion of “De errore” is devoted to portraying pagan deities as not only false but morally corrupting influences on their worshippers. Firmicus delves into the mythologies surrounding these deities, highlighting stories of deception, immorality, and violence to argue that the gods themselves are unworthy of reverence or imitation. This tactic serves not only to undermine the theological foundations of paganism but also to present it as a system that encourages vice rather than virtue.

Firmicus’s critique of pagan practices extends to the philosophical and theological underpinnings of these rituals. He contends that they are based on a flawed understanding of the cosmos, one that falsely attributes divine power and agency to the stars, natural phenomena, and statues made by human hands. By challenging the logic and efficacy of these practices, Firmicus seeks to demonstrate their futility and to contrast them with the Christian doctrine of a singular, omnipotent God who directly intervenes in the world out of love for humanity.

Beyond merely cataloguing the errors of paganism, Firmicus frames the rejection of pagan practices as a crucial step towards the spiritual and social renewal of the Roman Empire. He envisions Christianity as the means by which the empire can be reborn, grounded in a moral and ethical framework that promotes the well-being of its citizens. This vision extends to the socio-political realm, with Firmicus implying that the embrace of Christianity by the empire’s leadership and populace would lead to a more just and virtuous society.

The writing of “De errore” signifies Firmicus’s complete transformation and dedication to the Christian cause, marking his legacy as a fervent apologist of the faith. This work contributed to the growing body of Christian literature aimed at discrediting pagan traditions, thereby bolstering the intellectual and moral case for Christianity within the empire. “De errore” is not just a testament to Firmicus’s personal journey but also a strategic piece in the broader Christianisation of the Roman Empire, reflecting the increasingly polemical environment between pagan and Christian ideologies during this period (Salzman, Michele Renee, “The Making of a Christian Aristocracy”, Harvard University Press, 2002).

IV. The Dual Legacy of Firmicus Maternus: From Mathesis to Christian Apologetics

The dual legacy of Julius Firmicus Maternus, transitioning from an esteemed astrologer to a fervent Christian apologist, encapsulates a remarkable journey of intellectual and spiritual evolution during the transformative period of the late Roman Empire. This exploration delves into the philosophical and religious underpinnings of his works, particularly “Mathesis” and his Christian apologetic writings, to unravel how Firmicus served as a conduit of transition, mirroring and contributing to broader societal shifts.

“Mathesis”, a voluminous astrological compendium, epitomises Firmicus’s early engagement with pagan astrology. It reflects a sophisticated understanding of the cosmos, deeply entrenched in the prevailing philosophical and religious paradigms of its time. This work, rich in technical detail and theoretical exposition, showcases Firmicus’s adherence to the astrological tradition, asserting the influence of celestial bodies on human destiny (Firmicus Maternus, “Mathesis”, translated by Jean Rhys Bram, 1975). “Mathesis” embodies the culmination of pagan astrological knowledge, drawing from a plethora of sources to offer a comprehensive guide for interpreting astrological charts.

Within “Mathesis”, subtle philosophical inquiries hint at Firmicus’s burgeoning interest in themes central to Christian doctrine, such as divine providence, fate, and free will. Although primarily an astrological text, “Mathesis” occasionally reveals a tension between deterministic astrological predictions and the possibility of divine intervention. These thematic explorations set the stage for Firmicus’s eventual conversion to Christianity, indicating a deepening contemplation of the cosmos’s moral and spiritual dimensions beyond mere astrological determinism.

Firmicus’s conversion from an astrologer to a Christian apologist exemplifies his navigation through a period of profound religious and cultural transformation. The philosophical and theological inquiries embedded within “Mathesis” can be seen as a bridge to his later Christian writings. This transition is emblematic of the broader intellectual shift from a pagan to a Christian worldview, reflecting the complex interplay between traditional astrological practices and emerging Christian doctrine.

Firmicus occupies a unique position in the intellectual history of late antiquity, contributing significantly to both pagan and Christian discourses. “Mathesis” stands as a testament to the rich astrological tradition of paganism, while his Christian writings, particularly “De errore profanarum religionum”, critique and dismantle the pagan religious framework from a Christian perspective. Through his writings, Firmicus bridges the pagan past and the Christian future, offering insights into the transition of knowledge and belief systems in the late Roman Empire.

The personal transformation of Firmicus from an astrologer to a Christian apologist mirrors the larger cultural and religious transitions within the Roman Empire during and after the reign of Constantine I. Firmicus’s works reflect the dynamic interplay between the enduring presence of pagan traditions and the ascendancy of Christianity. His dual legacy illustrates the complex dynamics of religious and philosophical change in late antiquity, highlighting the fluidity of intellectual and spiritual identities in a period of significant transformation.

Firmicus Maternus’s journey from “Mathesis” to Christian apologetics encapsulates the broader narrative of the late Roman Empire’s transition from paganism to Christianity. His intellectual and spiritual evolution, mirrored in his writings, offers a unique lens through which to examine the interwoven paths of astrological knowledge and Christian belief. Firmicus not only embodies the personal and societal shifts of his time but also contributes to our understanding of the complex processes of cultural and religious transformation in late antiquity.

In contemporary discussions, Firmicus’s legacy continues to resonate, providing valuable insights into the intersections of faith, science, and cultural change. His transition from astrology to Christianity underscores the enduring questions about the nature of belief, the quest for truth, and the ways in which individuals and societies navigate the complex landscape of religious and philosophical identity. Firmicus Maternus’s life and works remind us of the dynamic interplay between personal conviction and cultural evolution, offering a poignant reflection on the challenges and possibilities of navigating change in any era.

Thank you for reading.

Fuel my caffeine addiction and spark my productivity by clicking that ‘Buy me a coffee’ button—because nothing says ‘I love this blog’ like a hot cup of java!

Buy Me a Coffee

Your Astrologer – Theodora NightFall ~

Your next 4 steps (they’re all essential but non-cumulative):

Follow me on Facebook & Instagram!

Subscribe to my free newsletter, “NightFall Insiders”, and receive my exclusive daily forecasts, weekly horoscopes, in-depth educational articles, updates, and special offers delivered directly in your inbox!

Purchase one of my super concise & accurate mini-readings that will answer your most pressing Astro questions within 5 days max!

Book a LIVE Astro consultation with me!