No products in the basket.

From Antiquity to Modernity: The Enduring Legacy of Hellenistic Astrologers in Contemporary Western Astrological Practices

Dear NightFall Astrology readers,

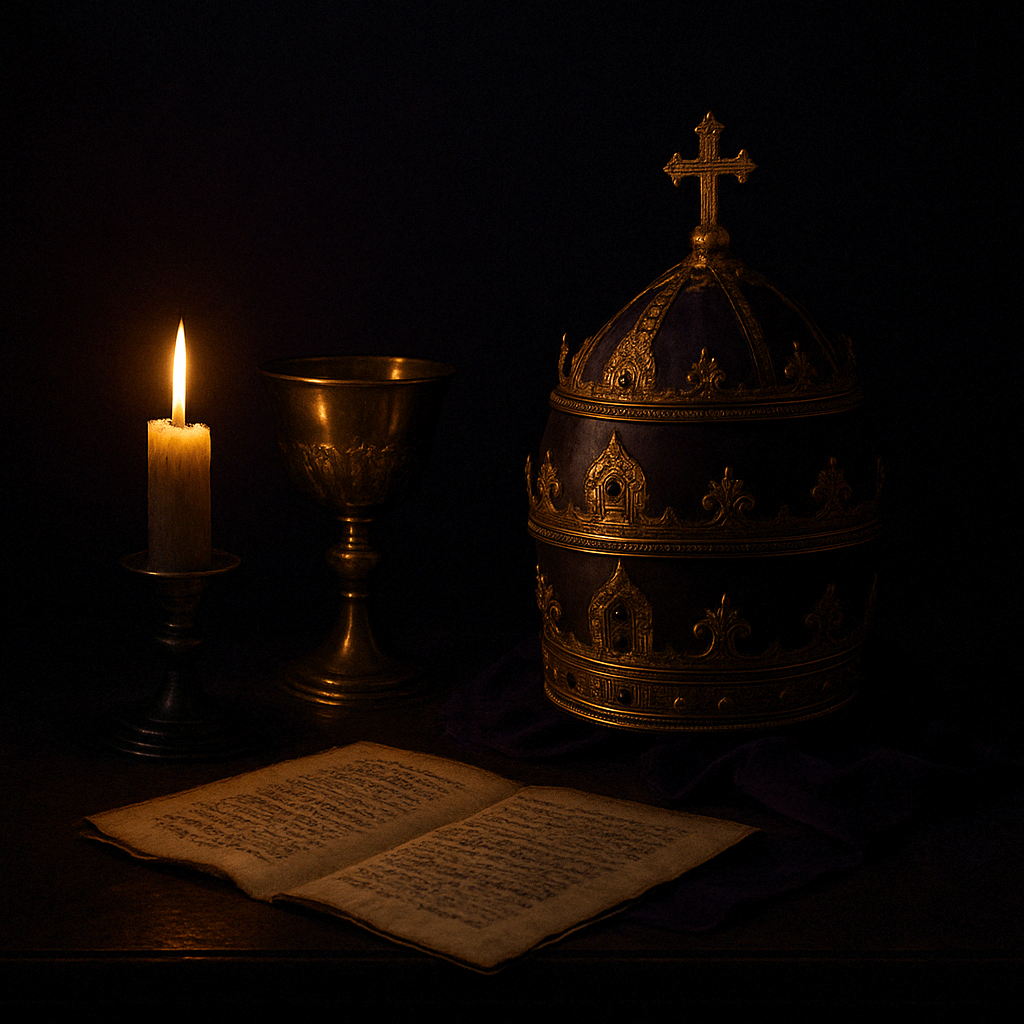

Astrology, an age-old practice, has undergone numerous transformations over the course of history. The timeline of its development is both rich and complex, starting with the earliest recorded Mesopotamian birth charts from 410 BC. This nascent stage of astrological thought later blossomed during the Hellenistic era, a period that began with Alexander the Great’s military campaigns in 334 BC and concluded with the Islamic conquest of Egypt in 639 AD. This era was a melting pot of astrological innovation, where Greek, Egyptian, and Mesopotamian traditions fused to create new systems and techniques.

The aim of this article is to explore the seminal contributions of key Hellenistic astrologers, contextualised within this captivating historical timeline. These pioneering figures have left an indelible impact on modern Western astrological practices, and their works continue to be of great relevance. As an astrologer, I find it essential to understand the roots of the techniques and philosophies that we use today, and this article seeks to illuminate those origins.

To bring you this narrative, I’ve delved into ancient manuscripts, consulted scholarly works, and examined historical records. The goal is to offer you a comprehensive yet accessible look at the subject, whether you’re a fellow practitioner or simply intrigued by the celestial patterns that have fascinated humanity for millennia.

I. Pre-Hellenistic Foundations:

Astrology’s historical roots are deeply embedded in various ancient civilisations, but a significant starting point is Mesopotamia. Contrary to popular belief, the oldest known Mesopotamian charts, dated to 410 BC, were not birth charts in the modern sense. Instead, they were more akin to electional or event charts, often created for significant events like the crowning of a king or the founding of a city. These charts were part of a broader astrological and divinatory tradition, deeply integrated into the religious and cultural fabric of the time (Rochberg, “The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture,” 2004; Brown, “Mesopotamian Astral Science,” 2000).

The next significant milestone in the development of astrology was the era of Alexander the Great. His conquests led to the founding of Alexandria in 334-332 BC, a city that would become a melting pot of various cultures and intellectual traditions, including astrology. Alexandria was home to the Great Library, which housed numerous astrological texts and served as a hub for scholars from various traditions to exchange ideas (Fraser, “Ptolemaic Alexandria,” 1972). The city became a focal point for the synthesis of Mesopotamian and Egyptian astrological traditions, laying the groundwork for what would later be known as Hellenistic astrology (Bowden, “Classical Athens and the Delphic Oracle: Divination and Democracy,” 2005).

In the early 3rd century BC, Berossus, a Babylonian priest and scholar, founded a school for astrology on the island of Kos. Berossus is credited with introducing Babylonian astrological methods to the Greek world, including the zodiac and the concept of horoscopy (Van der Waerden, “Science Awakening II: The Birth of Astronomy,” 1974). His school on Kos became a significant centre for astrological education and was instrumental in the dissemination of Babylonian astrological knowledge into the Hellenistic world (Sachs, “Babylonian Horoscopes,” 1998). Berossus’ work was not merely a translation of Babylonian astrology into Greek but a synthesis that enriched the existing Greek astrological practices with more systematic methods (Rochberg, 2004).

In summary, the pre-Hellenistic foundations of astrology are marked by a series of significant developments, starting with the oldest known Mesopotamian event charts, followed by the founding of Alexandria, and culminating in the establishment of Berossus’ school on Kos. Each of these milestones contributed to the complex tapestry of astrological knowledge and practice that would later be systematised and expanded upon by Hellenistic astrologers. These early foundations set the stage for astrology’s evolution into a sophisticated system of thought that continues to be studied and practised today.

II. The Dawn of Hellenistic Astrology:

The Hellenistic period marks a transformative era in the history of astrology, where various threads of astrological thought and practice were woven into a more systematic and comprehensive tapestry. One of the most intriguing artefacts from this period is the Antikythera Mechanism, dated to around 150 BC. This ancient Greek analogue computer was used for calculating astronomical positions and is thought to have astrological applications as well (Freeth et al., “Decoding the ancient Greek astronomical calculator known as the Antikythera Mechanism,” 2006). The mechanism signifies the advanced technical knowledge of the time and suggests a sophisticated understanding of celestial movements, which is foundational for astrological calculations.

By the mid-1st century BC, the last cuneiform astrological charts were being produced, and the first Greek birth charts began to appear. This transition marks a significant shift from the Mesopotamian tradition of event-based astrology to a more individual-focused natal astrology, which became a hallmark of Hellenistic and later Western astrology (Rochberg, “The Heavenly Writing,” 2004; Greenbaum, “Late Classical Astrology: Paulus Alexandrinus and Olympiodorus,” 2001).

Several key figures and texts from around 100 BC played pivotal roles in shaping what would become known as Hellenistic astrology. Among these, Hermes Trismegistus stands as a legendary figure often cited in astrological literature. He is associated with the fusion of Greek and Egyptian religious and philosophical ideas, encapsulated in what is often referred to as Hermeticism. While Hermetic astrology is attributed to him, it’s crucial to note that the historical existence of Hermes Trismegistus is a subject of scholarly debate. His contributions, whether real or apocryphal, are thought to include the integration of astrological symbolism with alchemical and magical practices, thereby enriching the interpretive framework of astrology (Fowden, “The Egyptian Hermes,” 1986).

Asclepius, another significant figure from this period, is often associated with medical astrology. His contributions are particularly noteworthy for linking celestial patterns to health and well-being. The Asclepius text, part of the Hermetic corpus, discusses the influence of celestial cycles on terrestrial events, including human health. This focus on medical astrology laid the groundwork for later astrological traditions that explored the relationship between planetary positions and medical conditions, a practice that continues in various forms today (Von Stuckrad, “Astrology and the Academy,” 2003).

Nechepso and Petosiris are two other figures often mentioned together in the context of Hellenistic astrology. They are credited with a seminal text that combined Egyptian and Babylonian astrological traditions. This text is considered foundational for Hellenistic astrology, particularly in the realm of natal astrology. It introduced a more systematic approach to horoscopic astrology, including the use of houses, aspects, and planetary periods. Their work laid the groundwork for later astrologers like Claudius Ptolemy, who would further systematise these techniques in his seminal work, the “Tetrabiblos.” The contributions of Nechepso and Petosiris were so influential that they were often cited by later astrologers as authoritative sources, and their methodologies have been preserved, albeit in fragmented forms, through citations in later works (Holden, “A History of Horoscopic Astrology,” 1996; Brennan, “Hellenistic Astrology: The Study of Fate and Fortune,” 2017).

In summary, the dawn of Hellenistic astrology was marked by significant advancements in both the technical and conceptual aspects of the field. The Antikythera Mechanism exemplifies the technical prowess of the age, while the transition from cuneiform to Greek birth charts signifies a shift in focus towards individual destiny. Figures like Hermes Trismegistus, Asclepius, Nechepso, and Petosiris contributed to a rich and complex astrological tradition that synthesised earlier Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Greek practices. Their contributions laid the foundation for the sophisticated system of Hellenistic astrology, which continues to influence modern astrological thought and practice.

III. The Roman Era & Beyond:

The Roman annexation of Egypt in 30 BC marked a pivotal moment in the history of astrology. This event signalled the end of the Ptolemaic dynasty and facilitated the spread of Hellenistic astrology into the Roman Empire. The Roman milieu, with its diverse cultural landscape and political reach, provided fertile ground for the evolution and institutionalisation of astrological practices (Barton, “Ancient Astrology,” 1994).

In the 1st century AD, Thrasyllus emerged as a significant figure in Roman astrology. Serving as the personal astrologer to Emperor Tiberius, Thrasyllus was not merely a practitioner but also an intellectual who contributed to the theoretical underpinnings of astrology. He is known for compiling and editing earlier astrological works, thereby helping to legitimise the practice within Roman intellectual and political circles. His influence was such that astrology became an accepted part of Roman statecraft during his time (Beck, “Planetary Types: The Science of Celestial Influence,” 2008).

Another luminary of this period was Manilius’ and his “Astronomica, which stands as a seminal work in the history of astrology, particularly for its role in bridging Hellenistic and Roman traditions. The text is comprehensive, covering a wide array of astrological topics such as the zodiac, planetary aspects, and houses. But beyond its scope, the influence of “Astronomica” can be seen in several concrete ways.

Firstly, Manilius’ work was one of the earliest to introduce astrological concepts to a Latin-speaking audience, thereby expanding the reach of astrology beyond its Greek and Egyptian roots. His Latin formulations of astrological concepts became standard references for later Latin scholars, such as Firmicus Maternus, who often cited Manilius in his own astrological treatise, “Mathesis” (Brennan, “Hellenistic Astrology: The Study of Fate and Fortune,” 2017).

Secondly, Manilius’ incorporation of Roman mythology and philosophy into astrological discourse was groundbreaking. For example, he used Roman deities to represent planets and signs, thereby making the subject more accessible and culturally relevant to a Roman audience. This syncretic approach helped integrate astrology into the broader fabric of Roman intellectual and cultural life (Green, “The Cambridge Companion to Latin Love Elegy,” 2013).

Thirdly, Manilius’ work laid the groundwork for the genre of didactic poetry in astrology. His poetic style made complex astrological theories more palatable and memorable, a technique later adopted by other astrological writers. This literary innovation helped disseminate astrological knowledge in a way that was both educational and engaging (Goold, “Manilius: Astronomica,” 1977).

Lastly, the methodologies and techniques described in “Astronomica” had a lasting impact on astrological practice. For instance, his explanations of planetary aspects and their significance in a natal chart became a standard part of astrological education and are still referenced in contemporary astrological practice (Holden, “A History of Horoscopic Astrology,” 1996).

Balbillus, active during the 1st century AD, was another influential astrologer, particularly in the court of Emperor Nero. He specialised in interrogational astrology, a branch concerned with casting charts for specific questions or events. Balbillus’ methods were considered highly accurate, earning him a place of esteem in the Roman court. His work in this area laid the groundwork for later developments in horary astrology, a sub-discipline that continues to be practised today (Lehoux, “What Did the Romans Know? An Inquiry into Science and Worldmaking,” 2012).

Antiochus of Athens, also from the 1st century AD, made significant contributions to the theoretical aspects of astrology. His extant work focuses on the foundational principles of astrology, including the roles and significations of planets, signs, and houses. Antiochus’ contributions were instrumental in shaping the technical language and conceptual framework of astrology, influencing not just his contemporaries but also later generations of astrologers (Holden, “A History of Horoscopic Astrology,” 1996).

In summary, the Roman era was a period of significant development and consolidation for astrology. The annexation of Egypt by Rome facilitated the spread of Hellenistic astrological knowledge, which was then adapted and expanded upon by Roman scholars and practitioners. Figures like Thrasyllus, Manilius, Balbillus, and Antiochus of Athens played pivotal roles in this process, each leaving an indelible mark on the field that continues to be felt today.

III. Dorotheus & Manetho:

Two figures who left an indelible mark on the astrological landscape during the Roman era are Dorotheus of Sidon and Manetho. Both made significant contributions to different branches of astrology, and their works have been cited, studied, and practised for centuries.

Dorotheus of Sidon, a pivotal figure in the late 1st century AD, made groundbreaking contributions to the field of electional astrology. His seminal work, “Carmen Astrologicum,” originally penned in verse, has been translated into multiple languages, including Arabic, and remains a cornerstone text for understanding classical electional techniques. Dorotheus’ work is lauded for its systematic approach, offering a comprehensive guide to electional astrology that covers a wide array of activities. For instance, he provided detailed guidelines for selecting auspicious times for marriage, suggesting specific planetary alignments that would signal a harmonious union. Similarly, his work delved into the intricacies of travel astrology, outlining how one could determine favourable times for voyages based on celestial configurations. His guidelines even extended to agriculture, advising on the best times for planting and harvesting based on lunar phases and planetary positions. Dorotheus’ methods often involved complex calculations, taking into account not just planetary positions but also lunar phases, fixed stars, and other celestial phenomena. His work laid the intellectual foundation for later astrologers like Hephaistio of Thebes and Paulus Alexandrinus, who expanded and refined his techniques in their own treatises (Pingree, “Dorothei Sidonii Carmen Astrologicum,” 1976).

Manetho, active in the early 2nd century AD, is another towering figure in the history of astrology, best known for his comprehensive treatise “Apotelesmatika.” Unlike Dorotheus, who specialized in electional astrology, Manetho’s work is a broad compendium that covers multiple branches of astrological practice, including natal, mundane, and electional astrology. The “Apotelesmatika” stands as one of the most systematic and exhaustive presentations of astrological knowledge from the Roman period. For example, in the realm of natal astrology, Manetho provided intricate details on how to interpret the planetary rulers of the houses in a birth chart, a technique that has been foundational in astrological practice. His work also delved into mundane astrology, offering insights into how celestial patterns could be interpreted to understand the fate of nations and rulers. Manetho’s influence extended far beyond his time, especially in the Byzantine and Islamic worlds. His work was translated into several languages and became a standard text for astrological education, laying the groundwork for the astrological traditions that followed (Brennan, “Hellenistic Astrology: The Study of Fate and Fortune,” 2017).

In summary, Dorotheus of Sidon and Manetho are pivotal figures in the history of astrology. Dorotheus’ contributions to electional astrology have had a lasting impact, providing a methodical framework that has been built upon by subsequent generations. Manetho’s “Apotelesmatika,” on the other hand, stands as a comprehensive guide to astrological practice, its influence rippling through various astrological traditions for centuries. Both works serve as foundational texts, shaping the practice and study of astrology well beyond their time.

IV. Ptolemy & Valens:

Two monumental figures in the annals of astrological history are Claudius Ptolemy and Vettius Valens, both active in the mid-2nd century AD. Their seminal works, “Tetrabiblos” and “Anthology,” have shaped the contours of astrological thought and practice for centuries.

Claudius Ptolemy, a distinguished polymath with a wide range of contributions in fields such as astronomy, geography, and music, is perhaps most celebrated for his astrological magnum opus, the “Tetrabiblos.” This seminal work sought to codify and systematise the astrological wisdom of the time, drawing heavily from both Babylonian and Egyptian traditions. Ptolemy was keen on establishing astrology as a rational discipline, arguing for its scientific legitimacy in parallel with other established fields like astronomy (Jones, “The Place of Astrology in the Philosophy of Claudius Ptolemy,” 1941).

A standout feature of the “Tetrabiblos” is Ptolemy’s intricate doctrine of planetary aspects, which refers to the angular relationships between planets in a chart. Ptolemy’s aspect doctrine was groundbreaking, as it introduced a systematic way to understand the interactions between planets based on their angular separations. This added a layer of complexity and nuance to astrological interpretation, allowing for a more detailed and insightful analysis of birth charts.

In addition to his aspect doctrine, Ptolemy also emphasised the natural qualities of planets, aligning them with the qualities of the four elements: fire, earth, air, and water. He described the planets in terms of being hot, cold, moist, or dry, integrating astrological symbolism with the prevailing humoral theory of his era. For instance, Mars was characterized as hot and dry, resonating with the fiery nature of the element it symbolises. This elemental framework, when combined with his aspect doctrine, provided a multi-faceted approach to interpreting planetary positions and relationships. It offered a rich tapestry of meaning that transcended mere celestial mechanics and has continued to influence astrological thought to this day (Brennan, “Hellenistic Astrology: The Study of Fate and Fortune,” 2017).

Vettius Valens, a contemporary of Claudius Ptolemy, made significant contributions to astrology through his work, the “Anthology.” Unlike Ptolemy, who was more focused on providing a theoretical and philosophical framework for astrology, Valens was deeply invested in the empirical aspects of the discipline. His work stands as a practical manual that delves into the nitty-gritty of astrological practice, offering a treasure trove of birth charts accompanied by meticulous interpretations. This makes the “Anthology” an invaluable resource for understanding the astrological techniques and methodologies employed during the 2nd century CE (Riley, “Vettius Valens: The Anthology,” 2022).

The scope of the “Anthology” is impressively broad, covering various branches of astrology including natal, electional, and even horary astrology, which is the art of answering specific questions by casting a chart for the moment the question is posed. Valens’ work is particularly rich in case studies, where he applied astrological techniques to real-life scenarios, thereby providing a form of empirical validation for the methods he described.

One of the most innovative aspects of Valens’ work is his introduction of specific astrological techniques that have had a lasting impact on the field. For instance, he made extensive use of the “Lots,” also known as Arabic Parts. These are calculated points in an astrological chart that are used for specific interpretations, such as the Lot of Fortune, which is often used to indicate matters related to prosperity and life’s ups and downs. Valens also delved into time-lord techniques, a set of methods used to determine periods during which specific planets would become activated or particularly significant in a person’s life. These techniques allowed astrologers to make more nuanced and timed predictions, adding depth to astrological interpretation (Schmidt, “Vettius Valens of Antioch,” 1994).

Valens’ “Anthology” also stands out for its pedagogical approach. He often presented multiple methods for achieving the same astrological calculation, providing astrologers with a range of tools and options. This not only showcased the diversity of astrological techniques available at the time but also allowed for a more tailored approach to astrological interpretation.

In conclusion, the works of Claudius Ptolemy and Vettius Valens serve as monumental pillars in the history of astrology, each contributing distinct yet complementary perspectives. Ptolemy’s “Tetrabiblos” laid the theoretical and philosophical groundwork, offering a systematic approach to astrological interpretation that has stood the test of time. His emphasis on planetary aspects and elemental qualities has enriched the field, providing a nuanced framework for understanding the celestial patterns that signal various life events and conditions. On the other hand, Valens’ “Anthology” stands as a practical compendium, rich in empirical data and case studies. His work has been instrumental in providing astrologers with a variety of techniques and methods, thereby enriching the practice with a level of detail and specificity that allows for more nuanced and timed interpretations. Together, these works encapsulate the intellectual rigour and empirical richness of astrological practice during the 2nd century CE, and their influence reverberates through the corridors of astrological thought and practice to this day.

V. Later Contributions & Transmissions:

The landscape of astrological thought did not remain static after the seminal contributions of Claudius Ptolemy and Vettius Valens. Several key figures emerged in the subsequent centuries, each adding layers of complexity and nuance to the existing body of knowledge.

Porphyry, a philosopher active in the 3rd century AD, is highly regarded for his “Introduction to the Tetrabiblos,” a companion piece to Claudius Ptolemy’s foundational astrological work. Among his most enduring contributions to astrology is his systematic approach to the astrological houses, specifically through what is now known as the “Porphyry House System,” a type of quadrant house system.

In astrology, houses serve to divide the celestial sphere into twelve segments, each corresponding to different areas of human life such as career, relationships, and health. While the concept of houses predates Porphyry, his quadrant-based system brought a new level of structure and specificity to this area of astrology. In the Porphyry House System, the degree of the Ascendant initiates the first house, and the degree of the Midheaven (Medium Coeli) marks the start of the tenth house. The arc between these two cardinal points is then equally trisected to determine the cusps of the second, third, eleventh, and twelfth houses. This method of division is one of the key features that distinguish it as a quadrant house system. This quadrant-based approach allows for a nuanced and context-specific interpretation of a natal chart.

Porphyry’s systematic treatment of the houses has had a lasting influence on astrological practice. It provided a consistent framework for interpreting the various life domains represented in a natal chart, offering astrologers a tool for more precise and meaningful analyses. The Porphyry House System remains a foundational element in astrological education and is still widely employed in contemporary astrological practice (Holden, “A History of Horoscopic Astrology,” 1996).

Antigonus of Nicea, a notable astrologer active in the 2nd century AD, holds a special place in the history of astrology for his pioneering work on interrogational astrology. This branch of astrology, which serves as a precursor to what is now commonly referred to as horary astrology, focuses on answering specific questions by analysing a chart cast for the moment the question is asked. Antigonus’ contributions in this area laid the groundwork for the development and refinement of horary techniques, providing a framework that has been built upon by subsequent generations of astrologers.

His writings on interrogational astrology offer a comprehensive guide to the principles and techniques used in question-based astrology. These include guidelines on how to frame questions, the significance of planetary positions at the time the question is posed, and the interpretation of these positions to arrive at an answer. His work also delves into the ethical considerations of question-based astrology, providing guidelines on what kinds of questions are appropriate to ask and which are not.

Antigonus’ contributions have been cited by later astrologers as a foundational text for understanding the nuances and methodologies of horary astrology. His work has been referenced in later treatises and continues to be studied as a valuable resource for anyone seeking to understand the principles of question-based astrology. The techniques and guidelines he established have been integrated into the broader practice of horary astrology, making his work a lasting part of the astrological canon (Brennan, “Hellenistic Astrology: The Study of Fate and Fortune,” 2017).

Firmicus Maternus, an astrologer active in the 4th century AD, is renowned for his extensive treatise “Mathesis,” which serves as a comprehensive guide to various astrological topics. One of the most significant aspects of his work is the in-depth treatment of natal astrology, the branch of astrology concerned with interpreting the natal chart of an individual to provide insights into their character, potential, and life path.

The “Mathesis” is a monumental work that spans eight books, each delving into different facets of astrology. However, it is the detailed exposition on natal astrology that has particularly stood the test of time. Firmicus Maternus goes beyond merely listing planetary significations; he provides a nuanced approach to interpreting the natal chart, offering guidelines on how to consider the interplay between planets, signs, and houses. His work also includes discussions on topics such as the Lots (also known as Arabic Parts), planetary periods, and the use of various predictive techniques within the context of a natal chart.

Moreover, Firmicus Maternus’ exploration of the ethical dimensions of astrological practice is a noteworthy aspect of his work that sets it apart from many other ancient astrological texts. In “Mathesis,” he delves into the responsibilities and ethical obligations that astrologers have towards their clients, emphasising the importance of integrity, confidentiality, and the responsible use of astrological knowledge. He argues that an astrologer should not only be proficient in technical calculations and interpretations but also be guided by a moral compass.

This ethical framework is not merely an addendum to his work but is integrated into the very fabric of his astrological philosophy. Firmicus outlines specific ethical guidelines, such as the importance of maintaining client confidentiality, avoiding fatalistic predictions that could cause undue distress, and the ethical implications of financial transactions in the astrological consultation process. He even touches upon the moral dilemmas that astrologers might face, such as whether or not to provide counsel that could potentially be used for nefarious purposes.

By incorporating these ethical considerations, Firmicus adds a layer of depth and complexity to his work that goes beyond the technicalities of astrological calculations and chart interpretations. It makes “Mathesis” a well-rounded treatise that serves as both a technical manual for astrological calculations and a guide to the ethical practice of astrology. This dual focus ensures that his work is not just a historical relic but a living document that continues to inform both the technique and ethics of modern astrological practice.

In this way, Firmicus Maternus elevates the practice of astrology to a discipline that requires not just intellectual acumen but also ethical integrity. His work serves as a reminder that the practice of astrology is not just about predicting outcomes but also about navigating the ethical landscape that comes with the power to provide potentially life-altering advice. This ethical dimension of his work has had a lasting impact, influencing modern codes of ethics in astrological organizations and continuing to be a subject of study and discussion among contemporary practitioners.

His work has been so influential that it continues to be a cornerstone text for astrologers specialising in natal astrology. The methodologies and techniques he outlined have been integrated into modern astrological practice, and his work is often cited in contemporary astrological education. It serves as both a foundational text for those new to the field and a reference work for more experienced practitioners (Greenbaum, “Matheseos Libri VIII,” 2011).

Paulus Alexandrinus and Hephaistio of Thebes, both luminaries in the astrological landscape of the 4th century AD, have left an indelible mark on the field of electional astrology. This branch of astrology focuses on choosing the most auspicious times to undertake various activities, from marriage and travel to business ventures and medical procedures. Both scholars built upon the foundational work of Dorotheus of Sidon, who was a pivotal figure in the development of electional astrology in the late 1st century AD.

Paulus Alexandrinus, in his work “Introductory Matters,” provided a systematic approach to electional astrology, offering a range of techniques for determining the most favourable times for different activities. His work is particularly noteworthy for its clarity and precision, making it accessible to both novice and experienced astrologers. Paulus introduced new methods for calculating planetary periods and transits, thereby allowing for more nuanced and timed predictions. He also offered detailed guidelines for interpreting the roles of the Moon and the Ascendant in electional charts, which have become standard considerations in contemporary practice.

Hephaistio of Thebes, on the other hand, is best known for his work “Apotelesmatics,” which also delves into electional astrology among other topics. Hephaistio’s contributions lie in his synthesis of earlier works, including those of Dorotheus and Paulus Alexandrinus, into a comprehensive treatise. He expanded upon their techniques by introducing additional considerations, such as the role of fixed stars and the importance of angular relationships between planets in electional charts. Hephaistio also provided a plethora of example charts to illustrate his techniques, making his work a practical guide for astrologers.

Both Paulus and Hephaistio were instrumental in refining and expanding the methods used in electional astrology. Their works served as bridges between the foundational contributions of Dorotheus and the later medieval and Renaissance astrologers who further developed these techniques. Their influence is evident in the continued relevance of their methods, many of which have been integrated into modern astrological software and are routinely taught in astrological curricula.

Olympiodorus the Younger and Rhetorius of Egypt, who were active in the 5th and 6th centuries AD, respectively, occupy a unique space in the history of astrology. While they were not the originators of new astrological techniques, their commentaries on earlier works have proven invaluable for scholars and practitioners alike in understanding the intricacies of Hellenistic astrology.

Olympiodorus the Younger, primarily known as a Neoplatonist philosopher, provided extensive commentaries on key astrological texts of his time. His work serves as a bridge between the philosophical underpinnings of astrology and its practical applications. Olympiodorus dissected complex astrological concepts and offered explanations that were rooted in Neoplatonic thought, thereby providing a philosophical context to astrological practice. His commentaries often clarified ambiguities in earlier texts and offered alternative interpretations that enriched the existing astrological knowledge. His work has been particularly useful for understanding the metaphysical aspects of astrology and how they relate to the more technical elements (Salzman, “Olympiodorus of Thebes and the End of Paganism,” 1994).

Rhetorius of Egypt, on the other hand, is best known for his “Compendium,” a compilation that not only summarised the astrological techniques of earlier masters but also included his own commentaries. Rhetorius had the advantage of hindsight, and his work reflects a synthesis of several centuries of astrological thought. His “Compendium” serves as an interpretive key for understanding a wide range of topics in Hellenistic astrology, from the significations of planets and houses to the complexities of timing techniques. Rhetorius also had the foresight to preserve several astrological techniques that were at risk of being lost, thereby serving as a guardian of astrological heritage.

Both Olympiodorus and Rhetorius acted as vital links in the chain of astrological tradition. Their commentaries have served as indispensable guides for decoding the complexities of Hellenistic astrology. They provided clarity, offered alternative viewpoints, and filled in gaps that might have otherwise been lost to history. In doing so, they contributed to the preservation and transmission of astrological knowledge, ensuring that the wisdom of earlier astrologers would be accessible to future generations. Their works remain important interpretive keys for anyone seeking to understand the depth and breadth of Hellenistic astrology.

The Islamic Empire’s conquest of Egypt in 639 AD stands as a watershed moment in the annals of astrological history. While it signalled the end of the Hellenistic astrological tradition as it was known, it also ushered in a new era of astrological scholarship and practice. Far from eradicating the existing astrological knowledge, Islamic scholars became the new custodians of this ancient wisdom. They undertook extensive translation projects, converting seminal Greek astrological texts into Arabic. This was part of a larger intellectual movement, often referred to as the Translation Movement, which aimed to preserve the scientific and philosophical achievements of the ancient world (Gutas, “Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early ‘Abbasid Society,” 1998).

Islamic scholars like Al-Kindi, Al-Farabi, and Avicenna played pivotal roles in this transformative period. They not only translated the works of Hellenistic astrologers but also wrote extensive commentaries and treatises that expanded upon these foundational texts. Their works often integrated astrological principles with Islamic philosophy and science, thereby creating a synthesis that was both respectful of tradition and innovative in its approach.

This period also saw the development of new astrological techniques and the refinement of existing ones. Islamic astrologers made significant contributions to various branches of astrology, including electional and mundane astrology, and their works often included advanced mathematical models that added a layer of sophistication to astrological calculations.

Moreover, the Islamic Empire served as a conduit for the transmission of astrological knowledge to medieval Europe. Through Spain and Sicily, which were Islamic territories at different periods, Arabic astrological texts were translated into Latin. This reintroduced astrology to Europe and set the stage for the Renaissance, where astrological thought would once again flourish.

Thus, the Islamic takeover of Egypt, while marking the end of the Hellenistic astrological tradition, was far from being its death knell. Instead, it served as a catalyst for the transformation and dissemination of astrological knowledge. Islamic scholars not only preserved the astrological wisdom of their Hellenistic predecessors but also enriched it, ensuring its continued relevance and application in subsequent periods. Their efforts laid the groundwork for the later developments in astrological theory and practice, making them an integral part of the rich tapestry of astrological history.

VI. The Enduring Legacy:

The legacy of Hellenistic and later astrologers in contemporary Western astrological practices is both enduring and significant. These ancient scholars laid the intellectual and methodological foundations that continue to inform modern astrology across its various branches, including natal, electional, and horary astrology.

Claudius Ptolemy’s “Tetrabiblos” is a seminal text that remains integral to astrological education today. His aspect doctrine and elemental framework provide a nuanced approach to interpreting planetary positions and relationships, and these methods are actively employed in modern astrological practice (Brennan, “Hellenistic Astrology: The Study of Fate and Fortune,” 2017).

Vettius Valens’ “Anthology” serves as a practical guide filled with birth charts and detailed interpretations. His innovative techniques, such as the “Lots” and time-lord systems, have had a lasting impact on the field, allowing for more nuanced and timed predictions (Riley, “Vettius Valens: The Anthology,” 1988; Schmidt, “Vettius Valens of Antioch,” 1994).

Firmicus Maternus’ “Mathesis” is noteworthy not only for its comprehensive treatment of natal astrology but also for introducing an astrologer’s oath, emphasizing the ethical responsibilities of astrologers towards their clients. This ethical dimension adds a layer of depth to his work and has influenced the ethical considerations in modern astrological practice (Greenbaum, “Matheseos Libri VIII,” 2011; Brennan, “Hellenistic Astrology: The Study of Fate and Fortune,” 2017).

Porphyry’s contributions to the systematisation of astrological houses, known as the Porphyry House System, have also stood the test of time and are foundational in astrological education (Holden, “A History of Horoscopic Astrology,” 1996).

The Islamic Empire played a pivotal role in preserving and translating these ancient texts, ensuring their survival and facilitating their transmission to medieval Europe and beyond (Gutas, “Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early ‘Abbasid Society,” 1998).

In summary, the enduring contributions of these astrologers are not merely historical artefacts; they continue to shape modern astrological practice in profound ways. Their techniques and philosophies, including the ethical guidelines laid down by Firmicus Maternus, serve as both a rich resource and a guiding framework for contemporary astrologers. This enduring legacy attests to the depth and sophistication of astrological thought, affirming its relevance across both time and culture.

Thank you for reading.

Fuel my caffeine addiction and spark my productivity by clicking that ‘Buy me a coffee’ button—because nothing says ‘I love this blog’ like a hot cup of java!

Buy Me a Coffee

Your Astrologer – Theodora NightFall ~

Your next 4 steps (they’re all essential but non-cumulative):

Follow me on Facebook & Instagram!

Subscribe to my free newsletter, “NightFall Insiders”, and receive my exclusive daily forecasts, weekly horoscopes, in-depth educational articles, updates, and special offers delivered directly in your inbox!

Purchase one of my super concise & accurate mini-readings that will answer your most pressing Astro questions within 5 days max!

Book a LIVE Astro consultation with me!