No products in the basket.

From Alchemy to Astrology: The Interconnected Practices of the Medieval & Renaissance Periods

Dear NightFall Astrology readers,

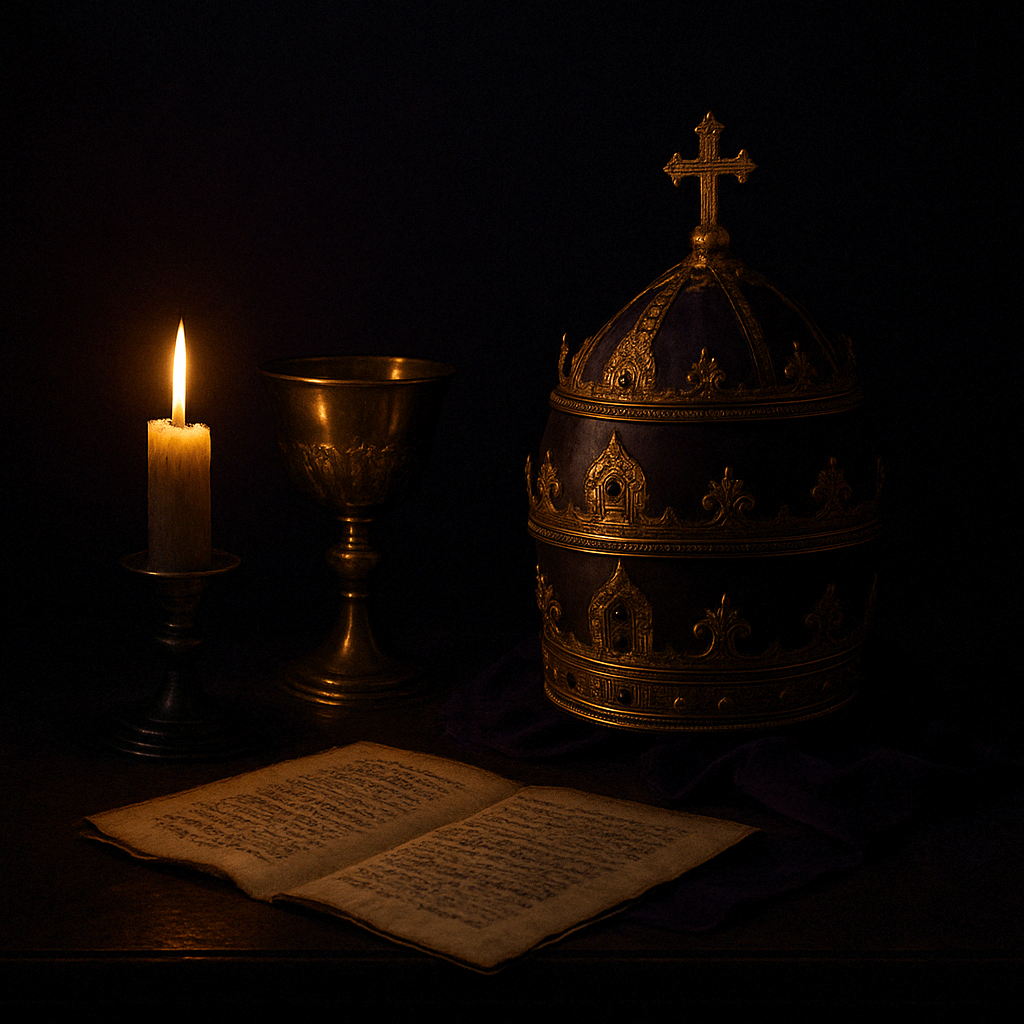

In a dimly lit chamber of a medieval scriptorium, an alchemist toils away with crucibles and alembics, pursuing the transmutation of base metals into gold. Concurrently, in an adjoining alcove, an astrologer scrutinises celestial charts, seeking to interpret the unfolding narratives of the stars. Though these two practitioners appear to be operating within distinct frameworks, they are, in fact, linked by a rich tapestry of intellectual, philosophical, and spiritual paradigms that characterised the Medieval and Renaissance periods.

Historically, the Medieval epoch was characterised by a theocentric worldview, wherein religious orthodoxy delineated the boundaries of intellectual endeavours. With the advent of the Renaissance, however, a shift occurred towards humanism, accompanied by burgeoning inquiries into the natural and celestial worlds. Throughout both periods, alchemy and astrology served as substantive arenas for the exploration of nature, spirituality, and the human condition, thereby warranting a nuanced examination.

The significance of scrutinising alchemy and astrology transcends historical intrigue; these disciplines represent a foundational scaffold upon which much of modern science and metaphysical inquiry have been constructed. They offer invaluable perspectives into the preoccupations that have perennially beset humanity: from the quest for immortality and well-being to the timeless endeavour to align terrestrial activities with celestial phenomena.

The central thesis of this article posits that alchemy and astrology were inextricably connected disciplines, mutually shaped by and shaping the spiritual, cultural, and intellectual landscapes of their respective epochs. This exploration will encompass an analysis of the historical backdrop against which they flourished, a detailed examination of seminal figures in each field, and an inquiry into the doctrinal and practical intersections between the two disciplines. Furthermore, the article will delineate the challenges and controversies that both fields encountered in their evolution.

In navigating this complex landscape, the article aims to unearth the profound and enduring impact that these oft-misunderstood disciplines have imprinted upon the intellectual and cultural history of humanity.

I. Historical Context:

The Medieval period, commonly dated from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in AD 476 to approximately the end of the 14th century, was a time when European society was under the aegis of feudalism and the Roman Catholic Church (Brown, P. “The World of Late Antiquity”). Intellectual activities were primarily aimed at spiritual understanding and were often couched in religious terminology (Southern, R.W. “Scholastic Humanism and the Unification of Europe”). Within this societal framework, scholasticism emerged as the prevailing intellectual tradition, a method steeped in theological inquiry and the writings of early Christian philosophers like Augustine and Anselm, as well as classical figures like Aristotle (Weisheipl, J.A. “The Development of Physical Theory in the Middle Ages”).

During the Medieval and Renaissance periods, alchemy and astrology were often viewed as legitimate means to fathom the natural and divine order. Alchemy was particularly seen as a kind of ‘sacred chemistry,’ an endeavour to decipher the divine essence inherent in natural substances (Newman, W.R. “Promethean Ambitions”). Astrology, despite meeting scepticism, found considerable utility among scholars affiliated with the church. For instance, Albertus Magnus, a Dominican friar, engaged in extensive writing on astrology, positing it as a tool for interpreting divine omens rather than as a deterministic system (Resnick, I.M. “Albertus Magnus and the Sciences”). Roger Bacon, a Franciscan friar, adopted a cautious yet supportive stance, advocating for the responsible practice of astrology and its reconciliation with Christian doctrine. He underscored the importance of empirical verification in the astrological practice, effectively merging it with elements of the scientific method (Crombie, A.C. “Robert Grosseteste and the Origins of Experimental Science”). These scholars exemplify the nuanced relationship between the church and astrology, revealing how ecclesiastical viewpoints could co-exist with, and even embrace, the intellectual currents of the time (Tester, S.J. “A History of Western Astrology”).

“In the transitional era of the Renaissance, which generally covered the period from the 14th to the early 17th centuries, the intellectual climate underwent a monumental shift. The rise of Humanism as a philosophical underpinning espoused individualism, empirical inquiry, and a resurgence of interest in classical literature and arts (Kristeller, P.O. “Renaissance Thoughts and the Arts”). Prominent figures such as Petrarch and Erasmus extolled the virtues of human potential and the importance of classical knowledge.

This epoch also heralded the beginning of the scientific revolution, thereby infusing the scholarly landscape with a newfound ethos of intellectual freedom and scepticism (Shapin, S. “The Scientific Revolution”). Pioneering minds like Nicolaus Copernicus and Galileo Galilei began to challenge traditional cosmological views, using observational data to inform their theories.

Amidst these broader shifts, alchemy began to morph from a focus on spiritual symbolism to a more empirical domain that laid the groundwork for modern chemistry. Pioneering alchemists such as Paracelsus and Robert Boyle shifted the lens from metaphysical pursuits to proto-chemical experimentation. They introduced the use of accurate measurements and scientific rigour, a transformation symbolised by Boyle’s formulation of the Gas Law (Principe, L.M. “The Secrets of Alchemy”).

Similarly, astrology was redefined during this transformative period. While medieval astrology had been more generalised, Renaissance astrology became increasingly analytical and personalised. Technological advancements in astronomical observation, made possible through the telescope’s invention and Tycho Brahe’s meticulous data, influenced astrological practice. This newfound precision made astrology more targeted, as it incorporated detailed astronomical charts in its analyses (Carey, H.M. “Courting Disaster: Astrology at the English Court and University in the Later Middle Ages”).

The embrace of empirical methodologies in both alchemy and astrology marked a significant departure from their historical roots, adapting to the intellectual paradigms of the time. In doing so, both fields served as both participants in, and products of, the intellectual currents of the Renaissance.

The historical contexts of the Medieval and Renaissance periods were instrumental in shaping the disciplines of alchemy and astrology. While rooted in theological soil during the Medieval period, both practices evolved to embrace more empirical and individualistic paradigms in the Renaissance. These shifts are not merely of historical interest but elucidate the complex interplay between spiritual belief, scientific inquiry, and societal norms. Subsequent sections will probe deeper into how these two practices were interconnected, reflecting the intellectual milieu of their respective epochs.

II. Alchemy in Focus:

Alchemy is a multi-faceted discipline, intricately tied to both the spiritual and material realms. Originating in Hellenistic Egypt and later spreading to Islamic and Christian worlds, alchemy primarily concerned itself with the transformation of substances, specifically the quest to turn base metals into noble metals such as gold (Holmyard, E.J. “Alchemy”). Central to this practice were elemental principles—earth, water, air, fire—and the concept of the Philosopher’s Stone, a substance believed to facilitate transmutation and grant eternal life (Principe, L.M. “The Secrets of Alchemy”).

Two seminal figures in the annals of alchemy are Geber, an 8th-century Islamic alchemist, and Paracelsus, a 16th-century Swiss physician and alchemist. Geber, also known as Jabir ibn Hayyan, is widely considered one of the founding fathers of alchemy and chemistry. His contributions, specifically in his seminal work ‘Book of the Composition of Alchemy,’ laid down the principles of the discipline and made significant advancements in experimental methods. These works were instrumental in shaping Islamic alchemy and were later translated into Latin during the 12th century, thereby profoundly influencing the trajectory of European alchemical thought (Kraus, P. “Jābir ibn Hayyān”).

In contrast, Paracelsus emerged in the backdrop of the Renaissance, at a time when alchemy was beginning to intermingle with empirical science. Paracelsus was a vociferous critic of the medical orthodoxy of his day, particularly the reliance on the works of Galen and Avicenna. He proposed a revolutionary idea of utilising alchemy in medical treatment, moving away from theory-driven approaches to one grounded in experimentation and observation. Central to Paracelsus’ alchemical philosophy was the concept of the ‘Three Primes’: salt, sulphur, and mercury, which he believed were foundational elements constituting both the material and immaterial worlds. This idea significantly influenced later alchemical and medical theories, heralding a shift towards a more empirically grounded approach (Webster, C. “Paracelsus: Medicine, Magic and Mission”).

Both Geber and Paracelsus were instrumental in shaping the development of alchemy, albeit in different periods and cultural contexts. Geber’s works laid the theoretical foundations, influencing European scholars who would later translate and build upon his ideas. Paracelsus, on the other hand, challenged existing norms, infusing alchemy with a new, more empirical focus, thereby catalysing its eventual evolution into modern chemistry.

John Dee, a 16th-century English polymath, occupies a unique position in the history of both alchemy and astrology. Not merely a dabbler, Dee was deeply embedded in the academic and royal circles of Elizabethan England, serving as an advisor to Queen Elizabeth I and actively participating in early modern scientific dialogues (Harkness, D. “John Dee’s Conversations with Angels”). His works encompassed a broad range of subjects, including mathematics, navigation, and hermetic philosophy, but he is most famously known for his interest in alchemy, astrology, and esoteric traditions.

Dee was a practitioner of alchemy and held it in high regard, not just as a proto-science but also as a spiritual discipline. His alchemical writings show a commitment to understanding the natural world as a reflection of divine principles, a viewpoint aligned with the broader Renaissance resurgence of Hermetic and Neoplatonic thought (Clulee, N. H. “John Dee’s Natural Philosophy: Between Science and Religion”).

In the realm of astrology, Dee was a rigorous theoretician. His astrological consultations weren’t limited to individual horoscopes; he employed astrology for a variety of purposes, including medical diagnosis and even national politics. He was known to have used astrological calculations to select auspicious dates for Queen Elizabeth I’s activities, indicating the degree to which astrology was integrated into the socio-political fabric of the time (French, P. “John Dee: The World of an Elizabethan Magus”).

What sets Dee apart is his effort to unify seemingly disparate fields — religious, esoteric, and empirical. He viewed alchemy and astrology as complementary routes to understanding both the material and celestial realms, hence working towards a kind of synthesis between science and spirituality that was quite avant-garde for his time (Szönyi, G. E. “John Dee’s Occultism: Magical Exaltation Through Powerful Signs”).

Thus, John Dee remains an emblematic figure, embodying the complexities and tensions of a period straddling medieval mysticism and the dawn of empirical science, actively contributing to both the legitimisation and the critique of the disciplines he practised.

Within the theocentric framework of Medieval Europe, alchemy was imbued with spiritual symbolism. Processes such as calcination and distillation were viewed as metaphors for spiritual purification and enlightenment (Newman, W.R. “Promethean Ambitions”). Furthermore, alchemy existed in a complex relationship with Christian doctrine. While some ecclesiastical authorities viewed it with suspicion, others endorsed its pursuit as a means to understand the divine order of nature (Linden, S.J. “The Alchemy Reader: From Hermes Trismegistus to Isaac Newton”).

With the advent of the Renaissance, alchemy underwent a significant transformation. The emerging ethos of humanism and empirical observation led to a more practical emphasis in alchemical practice (Principe, L.M. “The Secrets of Alchemy”). Alongside the traditional goals of transmutation and the search for the elixir of life, alchemy began to orient towards proto-chemical experimentation. This period also witnessed the beginnings of a terminological shift, with the word “chemistry” gradually being introduced to describe more empirical, laboratory-based investigations of matter (Newman, W.R. & Principe, L.M. “Alchemy vs. Chemistry: The Etymological Origins”).

III. Astrology in Focus:

The Babylonians played a foundational role in conceptualising astrology as a language of omens. Babylonian astrology primarily focused on celestial phenomena as portents of events on Earth, rather than causal agents (Rochberg, F. “The Heavenly Writing”). Enuma Anu Enlil, one of the most significant astrological texts from this period, is a testament to this view. It consists of omens associated with various celestial phenomena, positing no causative relationship but interpreting them as signs of future events (Brown, D. “Mesopotamian Planetary Astronomy-Astrology”).

In the Hellenistic period, astrologers grappled with two primary philosophical questions: whether celestial bodies acted as signs or causes, and the extent of determinism. Vettius Valens and Dorotheus of Sidon followed the Babylonian tradition of viewing celestial bodies as symbolic omens. Valens leaned towards a more deterministic perspective, whereas Dorotheus suggested partial determinism, where fate was seen as somewhat negotiable (Greenbaum, D.G. “Late Classical Astrology”).

On the other hand, Ptolemy and Firmicus Maternus adopted a causative view. Ptolemy advocated for partial determinism, allowing for human agency to mitigate celestial influences (Tester, S.J. “A History of Western Astrology”). Firmicus was strictly deterministic, considering fate unalterable (Holden, J.H. “A History of Horoscopic Astrology”).

{ If you’d like to learn more about these philosophical questions (astrology of signs or causes and determinism), check my extensive article on the subject HERE! }

In the Medieval period, Christian thought began to intersect with astrological beliefs. Thomas Aquinas and other scholastics aimed to reconcile Ptolemaic partial determinism with Christian free will (Tester, S.J. “A History of Western Astrology”). Guido Bonatti and Jean-Baptiste Morin took a deterministic stance, adjusting it to be compatible with Christian concepts of Divine Will and predestination (Holden, J.H. “A History of Horoscopic Astrology”).

The Renaissance breathed new life into astrology. Influenced by humanism, astrologers like John Dee combined Hermetic and Neoplatonic ideas with deterministic and sign-based astrological theories (Clulee, N.H. “John Dee’s Natural Philosophy”). William Lilly, a prominent figure in horary astrology, argued that while celestial bodies might indicate possible futures, human actions could change outcomes (Lilly, W. “Christian Astrology”).

Francesco Giuntini strove to blend Ptolemaic and Aristotelian concepts with the prevailing religious sentiments of his time (Campion, N. “A History of Western Astrology Volume II”). Like his Medieval predecessors, Giuntini believed in deterministic elements but placed ultimate power in divine providence (Tester, S.J. “A History of Western Astrology”).

The period also saw a surge in medical astrology. Paracelsus incorporated astrology into his holistic approach to medicine, acknowledging a partial determinism wherein celestial positions might indicate health tendencies but were not conclusive (Kassell, L. “Medicine and Magic in Elizabethan London”).

In summary, the philosophical underpinnings of astrology laid down during the Babylonian and Hellenistic periods found new expressions and adaptations in the Medieval and Renaissance eras, moulded by the prevailing socio-cultural and spiritual climates of the times (Campion, N. “A History of Western Astrology Volume II”).

IV. Interconnectedness of Alchemy & Astrology:

As we’ve seen, both alchemy and astrology were shaped by the prevailing philosophical frameworks of their respective times. Notably, Neoplatonism and Hermeticism played significant roles in shaping both practices. Neoplatonism provided a hierarchical worldview where every material object had a spiritual counterpart, resonating well with the alchemical quest to transmute base metals into gold and the astrological belief in planetary significations (Hornung, E. “The Secret History of Western Esotericism”). Hermeticism extended this worldview, emphasising spiritual rebirth and enlightenment, an end goal for many alchemists and astrologers alike (Goodrick-Clarke, N. “The Western Esoteric Traditions”).

Alchemy and astrology are ancient disciplines with roots that reach back to antiquity, particularly in Mesopotamia and Egypt. Their transformations through various epochs have been guided by shared philosophical foundations, and they have consistently intertwined in both theory and practical application. Existing in a liminal space between science, religion, and mysticism, these esoteric arts have found common ground in numerous ways. A notable illustration of this intricate relationship is John Dee’s “Monas Hieroglyphica,” a glyph that not only epitomises the unity of celestial and earthly dynamics but also serves as a comprehensive guide for both alchemists and astrologers.

In terms of practical intersections, it’s essential to highlight the role of astrological timing, calculated based on celestial movements, as an indispensable tool for Renaissance alchemists. These alchemists often consulted astrological calendars to determine the most propitious times for their alchemical operations (Prinke, R. T. “Alchemy and Astrology in the Renaissance”). Likewise, astrologers have utilised alchemical concepts to inform their practice, particularly in astrological medicine, which employs alchemically-prepared substances to balance bodily humours in accordance with planetary influences (Willis, R. and Curry, P. “Astrology, Science, and Culture”). This enduring symbiosis between alchemy and astrology underscores their mutual evolution and the multifaceted roles they have played in the intellectual and spiritual history of humanity.

Both alchemy and astrology had extensive cultural impacts beyond their immediate practical applications, infiltrating art, literature, and social discourse. For instance, alchemical symbolism and astrological allegory were commonplace in medieval and Renaissance art and manuscripts. Artists like Botticelli and writers like Chaucer employed these themes, subtly encoding the knowledge within their works (Eco, U. “Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages”).

The ethical considerations these disciplines generated were not dissimilar either. Both were scrutinised through the lens of Christian doctrine—alchemy for its potential heresy in attempting to mimic God’s creation and astrology for pre-empting divine will. Yet, both also found defenders who articulated their compatibility with Christian orthodoxy. Here, we see a resurgence of the same discussions around determinism and omens that we observed in earlier eras. Medieval astrologers like Bonatti and Renaissance figures like John Dee argued that these practices were not fatalistic but rather ways to understand divine intent (Tester, S. J. “A History of Western Astrology”).

The interconnectedness of alchemy and astrology thus embodies a unique blend of philosophy, practicality, and cultural significance. These disciplines were not isolated practices but were deeply intertwined in both conceptual foundations and practical applications, bearing the weight of ethical and social considerations that remain topics of discussion even today.

By examining their shared foundations and parallel journeys, we can better understand how each reflects larger spiritual and intellectual currents of their eras, enriching our broader understanding of medieval and Renaissance worldviews.

V. Challenges & Controversies:

Both alchemy and astrology have had complex relationships with religious institutions over the centuries, often being met with scepticism or outright condemnation. St. Augustine, an influential Christian theologian of the early 5th century, criticised astrology in his seminal work, ‘City of God.’ His primary argument was that astrology, by professing a form of determinism, contravenes the Christian doctrine of free will, making it incompatible with the faith (St. Augustine, “City of God”). St. Augustine’s views were highly influential and set the tone for later Christian perspectives on astrology.

In the Middle Ages, ecclesiastical opposition to astrology persisted. Thomas Aquinas, a 13th-century Christian scholar, allowed for a limited acceptance of astrology, provided it did not encroach upon individual free will or divine omnipotence. Despite this, the Church often frowned upon astrological practices, particularly when they appeared to influence political decisions or public opinion (Grant, E. “Planets, Stars, and Orbs: The Medieval Cosmos, 1200–1687”).

When it comes to alchemy, its goals of transmutation and the pursuit of the Philosopher’s Stone were viewed with suspicion by religious authorities. Alchemists were often accused of heresy or of attempting to ‘play God,’ challenging the divine order established by the Creator. The influential theologian Albertus Magnus, for instance, was more accommodating of alchemy but still warned against practices that seemed to go against the natural order or God’s will (Newman, W. R., “Promethean Ambitions”). By the time of the Renaissance, papal bulls were issued against certain alchemical practices, cementing the Church’s scepticism toward the discipline (Principe, L. M., “The Secrets of Alchemy”).

Over the years, the tension between these esoteric disciplines and religious institutions has not entirely dissipated. Even in the modern era, various religious groups maintain positions that are either cautious or dismissive of astrology and alchemy, viewing them as either superstitious or as pseudo-sciences (Tester, S. J., “A History of Western Astrology”).

The rise of empirical science during the Enlightenment posed another set of challenges. Alchemy was gradually superseded by chemistry, which prided itself on replicable experiments and standardised methodologies (Newman, W. R., “Alchemy Tried in the Fire”). Astrology, too, felt the brunt of the scientific revolution. Kepler and Galileo, both of whom had astrological leanings, contributed to a cosmology that increasingly left little room for astrological causality (Kuhn, T. S., “The Copernican Revolution”).

Within each discipline, internal debates raged, refining approaches and sometimes altering core tenets. Alchemists disagreed on the use of particular substances and the interpretation of esoteric texts, leading to the emergence of diverse alchemical traditions (Principe, L. M., “The Secrets of Alchemy”). Astrologers were similarly divided. As we’ve seen, Medieval and Renaissance astrologers found themselves at a crossroads between viewing celestial bodies as omens or causes, much like their Hellenistic predecessors. Their views adapted in response to religious scrutiny and the rise of empirical science, leading to modern forms of astrology that often emphasise psychological archetypes (Campbell, P. “From Ancient Omens to Statistical Mechanics”).

These challenges and controversies, far from relegating alchemy and astrology to the annals of history, have been instrumental in shaping their evolution, ensuring that they remain vibrant and complex disciplines that continue to captivate the intellectual and spiritual imagination.

This article has traversed the complex tapestry of alchemy and astrology, elucidating their historical foundations, key figures, and philosophical underpinnings. We delved into the intricacies of their relationships with religious and scientific establishments, as well as internal conflicts that have shaped their evolution.

Many questions remain unanswered. The exact influence of Neoplatonism on both alchemy and astrology, for example, warrants deeper scholarly attention. Furthermore, the shift from deterministic to symbolic interpretations, particularly during transitional periods like the Renaissance, also begs further study.

Alchemy and astrology are not relics of a bygone era, but rather evolving disciplines that continue to intrigue us. Their ability to adapt and morph under religious, scientific, and internal scrutiny underlines their resilience and enduring appeal. Through a nuanced understanding of their past, we can more richly appreciate their contemporary manifestations. Whether viewed as arcane arts or psychological sciences, alchemy and astrology occupy a unique place in human thought—a place where the empirical meets the enigmatic, and the rational converges with the mystical.

This concludes our intellectual journey, but it is by no means the final word on these fascinating subjects.

Thank you for reading.

Fuel my caffeine addiction and spark my productivity by clicking that ‘Buy me a coffee’ button—because nothing says ‘I love this blog’ like a hot cup of java!

Buy Me a Coffee

Your Astrologer – Theodora NightFall ~

Your next 4 steps (they’re all essential but non-cumulative):

Follow me on Facebook & Instagram!

Subscribe to my free newsletter, “NightFall Insiders”, and receive my exclusive daily forecasts, weekly horoscopes, in-depth educational articles, updates, and special offers delivered directly in your inbox!

Purchase one of my super concise & accurate mini-readings that will answer your most pressing Astro questions within 5 days max!

Book a LIVE Astro consultation with me!