No products in the basket.

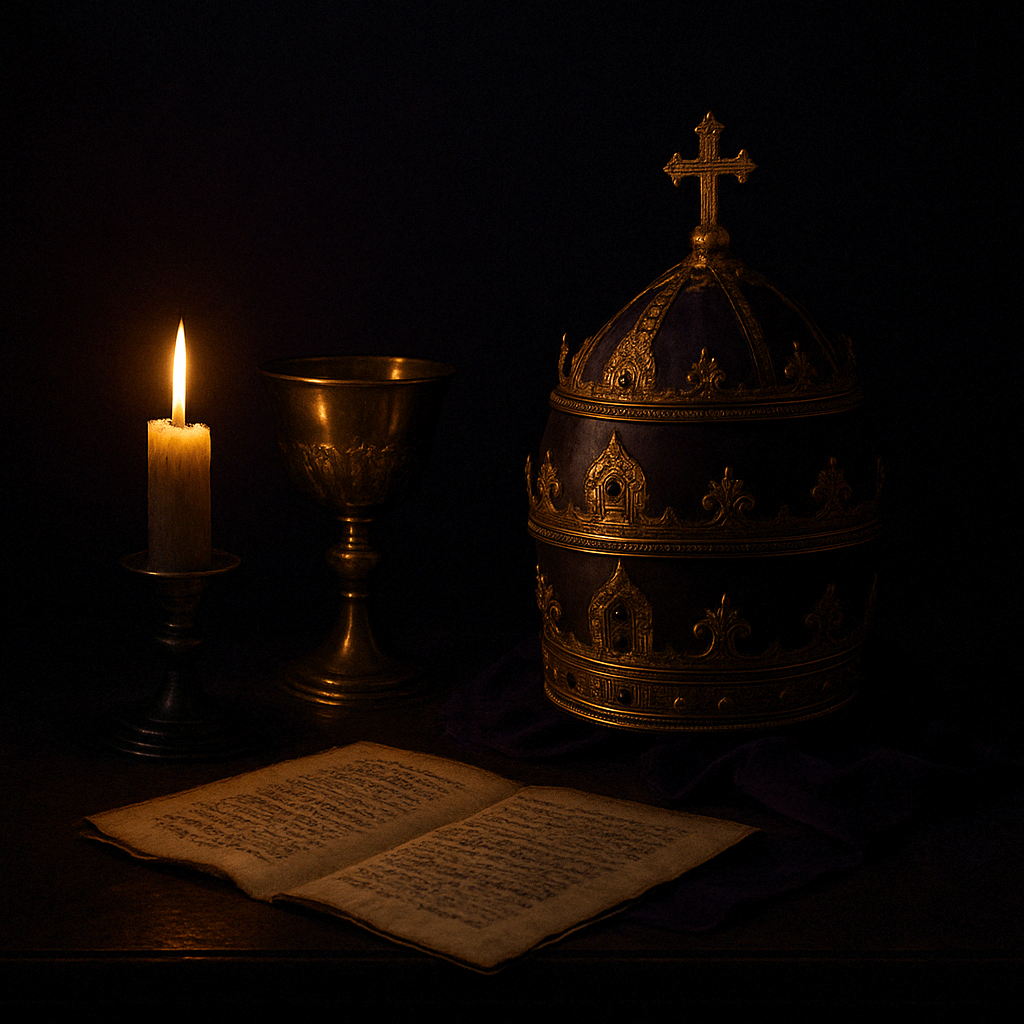

Astrology & the Church: A Complicated Relationship Through the Ages

Dear NightFall Astrology readers,

Astrology, a discipline as ancient as civilisation itself, has long held a mirror to the human quest for understanding the cosmos and its perceived connections to our terrestrial lives. Rooted in the belief that celestial bodies signal significant events and personal traits, astrology has been a constant companion in humanity’s cultural and intellectual journey. From the meticulous observations of Babylonian sky-watchers to the intricate astrological systems of Hellenistic Greece, this celestial art has woven its way through various cultures, each time intertwining itself with the prevailing philosophies and sciences of the era.

The relationship between astrology and the Church, however, presents a tapestry of complexity and contradiction. In the early days of Christianity, the Church Fathers grappled with astrology’s popularity and its philosophical implications. While some viewed it as a tool for understanding God’s creation, others condemned it as a practice steeped in superstition and fatalism. This dichotomy set the stage for a nuanced and often contentious relationship that evolved over the centuries. The Medieval Church saw astrology as both a necessary component of medical and scientific study, and a potential gateway to heretical thought. The Renaissance further complicated this relationship, as the Church found itself both patron and critic of astrological studies.

This article aims to explore the intricate and evolving relationship between astrology and ecclesiastical authorities. Tracing the journey from early Christian scepticism to medieval ambivalence, and from Renaissance intrigue to modern-day perspectives, it seeks to unravel the threads of acceptance, condemnation, and coexistence that have defined this relationship. Through a detailed examination of historical contexts, doctrinal shifts, and the ever-changing landscape of religious and astrological thought, we will gain a deeper understanding of how astrology and the Church have influenced and responded to each other through the ages. This exploration is not just a study of historical interactions, but also a reflection on the broader themes of belief, knowledge, and the enduring human desire to find meaning in the stars.

I. Historical Context of Astrology:

A. Astrology in Ancient Civilisations:

Astrology’s roots can be traced back to ancient civilisations, where it played a significant role in cultural and religious practices. In Mesopotamia, astrology began as a form of omen interpretation, with celestial phenomena seen as divine messages. This early form of astrology was integral to the governance and culture of Mesopotamia, influencing decisions of rulers and priests (Rochberg, 1998).

In Egypt, astrology was closely tied to mythology and religion. The movements of stars and planets were associated with gods, playing a significant role in agricultural practices and religious rituals. This approach to astrology was deeply symbolic, emphasising the cyclical nature of celestial events (Redford, 1992).

The Greeks further developed astrology, integrating it with their philosophical and scientific thought. This period saw the development of the zodiac system and the concept of the horoscope, reflecting the Greek focus on individualism and the human experience (Barton, 1994).

With the Roman Empire’s rise, astrology became a tool for personal guidance and imperial decision-making. Emperors like Augustus used astrology to legitimise their rule, embedding it further into society’s fabric. This widespread acceptance in the Roman world set the stage for its encounter with early Christian thought (Barton, 1994).

B. The Church Fathers & Astrology:

The early Christian Church’s stance on astrology was marked by a notable ambivalence, a sentiment vividly reflected in the writings of prominent Church Fathers. Augustine of Hippo, a key figure in early Christian theology, exemplified this ambivalence in his work “Confessions.” Augustine expressed scepticism about astrology, particularly its deterministic implications, arguing that such beliefs undermined the Christian doctrines of free will and divine providence. He critiqued the idea that celestial bodies could directly influence human affairs, yet he acknowledged their role as part of God’s harmonious creation (Brown, 1967).

This ambivalence was not unique to Augustine. Other early Church figures, such as Origen and Tertullian, also grappled with astrology’s place in Christian thought. Origen, for instance, while acknowledging the beauty of the celestial order, cautioned against interpreting this order as having direct influence over human destiny. Tertullian, on the other hand, was more outright in his opposition, viewing astrology as a pagan practice incompatible with the Christian faith.

The dichotomy in these early Christian perspectives significantly influenced the Church’s approach to astrology over the centuries. While some viewed astrology as incompatible with Christian teachings, others saw it as a valuable science revealing the workings of God’s creation.

The integration of astrology into medieval scholasticism marked a turning point. The 12th and 13th centuries, characterized by a resurgence in interest in natural philosophy and the sciences, saw astrology being studied in monasteries and universities, often with the Church’s tacit approval. This period witnessed the translation of key Arabic and Greek astrological texts into Latin, making them accessible to the Western scholarly community. Figures like Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas, while cautious, engaged with astrological ideas, integrating them into a Christian worldview within certain doctrinal boundaries (Tester, 1987).

In this historical context, astrology emerges as a dynamic field that adapted and evolved with the cultures that practiced it. From the early scepticism of Augustine to the more integrative approaches of medieval scholars, astrology’s journey through Christendom reveals a narrative of adaptation, integration, and, at times, conflict. This narrative sets the stage for understanding the multifaceted relationship between astrology and the Church in the subsequent centuries, highlighting the enduring interplay between faith, science, and the quest for understanding the cosmos.

II. The Medieval Church & Astrological Practice:

A. Astrology in Monastic Life & Learning:

During the medieval period, astrology carved out a significant niche within monastic life and learning. Monasteries, as pivotal centres of learning and knowledge preservation, played an instrumental role in the study and transmission of astrological knowledge. In these religious communities, astrology was often integrated with medical practices. Monks and other religious scholars used astrological charts to determine auspicious times for various medical procedures and the creation of medicinal remedies, a practice rooted in the belief that celestial movements had a bearing on bodily health and the efficacy of treatments (North, 1986). This integration of astrology into monastic medicine was influenced by the influx of ancient Greek and Arabic texts, which were diligently translated and studied within these religious institutions.

One notable example of this integration is the work of Hildegard of Bingen, a 12th-century Benedictine abbess known for her contributions to herbal medicine and natural history. Hildegard’s writings reflect an understanding of the influence of celestial bodies on human health, a perspective that was shaped by the astrological knowledge of her time.

The Church’s patronage of astronomical studies also had a significant impact on the development of astrology. In the medieval period, the distinction between astronomy and astrology was blurred, with both disciplines often seen as part of a unified study of the heavens. The Church, in its quest for practical knowledge, such as the calculation of the date of Easter, inadvertently fostered the study of astrology. Understanding the movements of celestial bodies was crucial for both astronomy and astrology, and the Church’s support for astronomical research provided a foundation for astrological studies (Hoskin, 1998).

An example of this intertwined study can be seen in the work of the 13th-century scholar Roger Bacon, a Franciscan friar who made significant contributions to the study of optics and astronomy. Bacon’s work, which was often conducted under the auspices of the Church, included astrological considerations, reflecting the interconnected nature of these disciplines during this period.

The work of medieval astronomers, many of whom were monks or clerics, laid the groundwork for later developments in both astronomy and astrology. Figures like the Venerable Bede, a 7th-century English monk, and later, the 14th-century astronomer Nicholas of Cusa, contributed to a growing body of knowledge that straddled the line between religious doctrine and scientific inquiry. Their work, supported and sometimes scrutinized by the Church, highlights the complex relationship between religious belief, scientific discovery, and the study of the stars during the medieval period.

B. The Condemnation & Acceptance Cycle:

The medieval Church’s relationship with astrology was characterized by a fluctuating cycle of condemnation and acceptance, reflecting the era’s complex intellectual and theological landscape. A prominent example of official condemnation is the Parisian Condemnations of 1277. Stephen Tempier, the Bishop of Paris, issued a list of propositions deemed heretical, including several statements related to astrology. This act was significant as it represented a clear stance by the Church against aspects of astrological practice that appeared to contradict Christian doctrine or infringe upon the realm of divine providence (Grant, 1996).

However, alongside these condemnations, there existed a nuanced acceptance of astrology in certain contexts. Astrological imagery was notably prevalent in church art and literature. Zodiac signs and planetary symbols were commonly featured in illuminated manuscripts, stained glass windows, and church decorations, reflecting a cultural acceptance and integration of astrological symbols (Katz, 1998). This juxtaposition of critique and integration highlights the Church’s complex relationship with astrology, where it was simultaneously viewed with suspicion and embraced as a cultural and artistic element.

Historical examples further illustrate this dichotomy. For instance, the works of Dante Alighieri, particularly in “The Divine Comedy,” integrate astrological concepts within a Christian framework, suggesting a level of acceptance and understanding of astrology’s cultural significance. Similarly, the 12th-century philosopher and theologian Peter Abelard, known for his critical and rational approach to theology, engaged with astrological ideas in his writings, reflecting the intellectual curiosity of the time.

Moreover, the Church’s stance towards astrology was not uniformly negative or dismissive. Figures like Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas, while cautious about astrology’s potential to contradict Christian teachings, did not outright reject the discipline. Instead, they sought to understand and delineate the boundaries within which astrology could be considered acceptable.

This period in history, therefore, illustrates the intricate balance the Church sought to maintain between upholding doctrinal purity and engaging with the prevalent intellectual currents of the time. The Church’s relationship with astrology during the medieval era was a dynamic interplay of acceptance, rejection, and adaptation, mirroring the broader societal and intellectual trends of the period.

III. The Renaissance & the Church’s Astrological Dilemma:

A. The Renaissance Rebirth of Astrology:

The Renaissance, a period marked by a profound intellectual and cultural awakening, heralded a significant resurgence in astrological studies, a revival that extended into ecclesiastical circles. This era, characterized by a renewed interest in classical knowledge, saw astrology regaining popularity among both the general populace and members of the clergy. The humanistic movement, with its emphasis on classical antiquity, played a pivotal role in this revival. Scholars and clerics, influenced by the rediscovery of ancient astrological and philosophical texts, began to perceive astrology as a discipline that could coexist with Christian teachings. The works of Ptolemy and other ancient astrologers were revisited, leading to a nuanced understanding of astrology as part of the broader tapestry of divine creation and human experience (Kieckhefer, 1989).

The Church’s role in the patronage of astrological research during the Renaissance was complex and multifaceted. Despite an official stance of caution, many churchmen, including those in high-ranking positions, became patrons of astrological studies. This patronage was driven not just by personal interest but also by a deeper theological and philosophical curiosity. These churchmen viewed astrology as a means to gain profound insights into the natural world, seen as a manifestation of divine order and wisdom. The Church’s involvement in the patronage of astrology during this period was indicative of a broader trend of seeking harmony between religious beliefs and emerging scientific perspectives.

Historical examples abound. Pope Sixtus IV, who commissioned the Sistine Chapel, was a notable patron of the arts and sciences, including astrology. He appointed the astrologer Johannes Müller von Königsberg, known as Regiomontanus, to reform the calendar, a task that intertwined astronomical and astrological knowledge. Similarly, Pope Julius II consulted astrologers for the election of his papal coronation date, reflecting the astrological influence in even the highest echelons of the Church.

Moreover, the era witnessed the flourishing of astrological works, with texts being commissioned and sponsored by church officials. The Vatican Library itself became a repository for many of these works, further embedding astrology into the intellectual fabric of the time. Figures like Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, both influential Renaissance humanists, engaged deeply with astrology. Ficino, in particular, attempted to reconcile astrology with Christian theology, arguing for a version of astrology that respected human free will while acknowledging the influence of the stars (Marrone, 1988).

Thus, the Renaissance marked a period of intellectual ferment where astrology, once relegated to the margins, was reexamined and integrated into the broader discourse of knowledge and belief. This period set the stage for the complex interplay between astrology and the Church, reflecting the era’s quest for a synthesis of ancient wisdom and contemporary understanding.

B. The Church’s Response to Astrological Practices:

The Church’s response to the burgeoning interest in astrology during the Renaissance was complex and often contradictory. The Inquisition, tasked with maintaining Church orthodoxy, scrutinized astrological practices with significant rigor. Astrologers, caught in the crosshairs of the Inquisition, frequently faced trials and tribulations, especially when their practices or predictions seemed to challenge the Church’s authority or contradict its doctrinal teachings. Accusations of heresy were not uncommon, as astrology, with its implications of predetermination, was perceived as potentially undermining the Church’s teachings on divine providence and human free will (Brooke, 1991).

Historical examples illustrate this tension. The case of Gerolamo Cardano, a renowned Italian astrologer and mathematician, exemplifies the precarious position of astrologers during this period. Despite his contributions to mathematics and medicine, Cardano’s astrological pursuits led to accusations of heresy and a subsequent trial by the Inquisition. Similarly, the famed astronomer and astrologer Johannes Kepler, known for his laws of planetary motion, also practiced astrology. While his scientific achievements were celebrated, his astrological work was viewed with suspicion by the Church.

Simultaneously, the Church engaged in a complex process of delineating acceptable astrological practices from those deemed heretical. This endeavour was far from straightforward, resulting in astrology’s fluctuating status between tolerance and censure. The Church’s primary concern was to prevent astrology from infringing upon the theological domains of divine providence and human agency. Astrological practices perceived as deterministic, suggesting fixed and unalterable human destinies, were particularly contentious.

The Renaissance era thus represents a critical juncture in the history of astrology’s relationship with the Church. Characterized by a revival of classical knowledge and a burgeoning humanistic spirit, this period saw renewed interest in and acceptance of astrology. However, this interest was met with a cautious and sometimes contradictory response from the Church. Efforts to maintain doctrinal purity often clashed with the growing fascination with astrological practices.

This era underscores the enduring tension between the pursuit of knowledge about the natural world and adherence to religious doctrines and beliefs. The Church’s response to astrology during the Renaissance reflects its broader struggle to navigate the changing intellectual landscape, balancing the preservation of traditional religious beliefs with the incorporation of new forms of knowledge and understanding.

IV. The Enlightenment to Modern Times:

A. The Decline of Astrological Influence:

The Enlightenment era, a pivotal period in the history of Western thought, marked a profound shift in the status of astrology, particularly within ecclesiastical and academic realms. This era, characterised by an emphasis on scientific rationalism, fostered growing scepticism towards astrology. Enlightenment thinkers, with their focus on empirical evidence and logical reasoning, increasingly viewed astrology as a relic of a superstitious past, incompatible with the emerging rationalist worldview. This scepticism was not confined to secular intellectuals but also permeated the Church. Aligning itself with burgeoning scientific thought, the Church began to distance itself from astrology, reflecting a broader societal shift towards an empirical and rational understanding of the natural world (Shapin, 1996).

Historical examples illustrate this shift. Figures like Isaac Newton, although deeply religious, contributed to a worldview where celestial phenomena could be explained through natural laws, without recourse to astrological interpretations. Newton’s laws of motion and universal gravitation provided a framework for understanding the movements of celestial bodies that was grounded in empirical observation and mathematical reasoning, challenging the traditional astrological worldview.

The decline of astrology’s influence was further accelerated by the development of new scientific disciplines, particularly astronomy and physics. These fields, emerging as distinct and rigorous areas of study, offered explanations for celestial phenomena that did not rely on astrological interpretations. This scientific advancement challenged the traditional astrological worldview, which had previously provided a framework for understanding celestial events in relation to human affairs.

The Church, in its pursuit to remain relevant and credible in an increasingly scientific world, gradually reduced its engagement with astrology. This reduction was part of a broader effort to align Church teachings with contemporary scientific knowledge, a move that was seen as essential for maintaining the Church’s intellectual and moral authority in a rapidly changing world (Brooke, 1991).

The Enlightenment thus represents a significant turning point in the history of astrology’s relationship with the Church. The era’s emphasis on empirical evidence and rational inquiry led to a reevaluation of many traditional beliefs, including astrology. The Church’s response to these changes was part of a larger process of adapting to the new intellectual landscape, a process that involved reconciling religious teachings with the advancements of science and rational thought.

B. Astrology’s Modern Resurgence & the Church’s Stance:

The 20th century marked a notable revival of interest in astrology, a phenomenon often linked with the rise of New Age movements and a renewed fascination with alternative spiritualities. This resurgence brought astrology back into the public consciousness, albeit in a new guise, often blending ancient practices with modern psychological and spiritual perspectives. However, the Church’s reaction to this revival was far from uniform. Within the ecclesiastical community, attitudes ranged from dismissive tolerance to outright condemnation. Some within the Church regarded astrology as a benign, though misguided, interest, akin to a hobby rather than a serious threat to Christian doctrine. Others, however, viewed it more critically, denouncing astrology as a practice that fundamentally contradicted Christian teachings. The deterministic implications of astrology, suggesting a preordained human destiny governed by celestial movements, were particularly troubling for those who emphasised the Christian doctrines of free will and divine providence (McGrath, 1999).

The diversity in the Church’s modern responses to astrology reflects the broad spectrum of perspectives within Christianity itself. Some denominations and theologians have been vocal in their criticism of astrology, labelling it as a form of divination that directly conflicts with biblical teachings. This opposition is often rooted in the belief that astrology, by its very nature, diverts believers from a Christ-centered faith and undermines the sovereignty of God in human affairs. On the other hand, a more nuanced approach has emerged in some Christian circles, acknowledging the historical and cultural significance of astrology. While these groups do not endorse astrology as a guide for life decisions or future predictions, they recognise its value as a symbolic language that can offer psychological insights or serve as a tool for self-reflection. This perspective, however, comes with a cautionary note: astrology should not supplant core Christian beliefs or practices, nor should it be used to predict or influence future events (Campion, 2009).

In the contemporary context, the Church’s stance on astrology continues to be diverse. Mainstream Christian thought generally maintains a sceptical view of astrology, prioritizing the concepts of free will and divine intervention over astrological determinism. Yet, there remains a subset within the Christian community that finds value in astrology as a metaphorical or symbolic system. This group views astrology not as a deterministic framework but as a means of personal exploration and spiritual growth, provided it does not contradict the fundamental tenets of Christianity (Campion, 2009).

The evolution of astrology from the Enlightenment era to modern times illustrates the shifting dynamics between religion, science, and alternative belief systems. The Church’s stance on astrology, evolving over time, mirrors broader societal trends in the approach to knowledge, belief, and the complex interplay between faith and reason. As society continues to grapple with these issues, the relationship between astrology and the Church remains a fascinating reflection of the ongoing dialogue between tradition and modernity, scepticism and belief, science and spirituality.

The relationship between the Church and astrology has been a complex and evolving one, marked by periods of acceptance, ambivalence, and rejection. From its early integration into monastic life and the medieval scholastic tradition to its decline during the Enlightenment and varied responses in modern times, astrology’s journey alongside ecclesiastical authorities reflects broader shifts in cultural, intellectual, and religious paradigms.

Underlying the Church’s stance on astrology are several key factors. The desire to uphold doctrinal purity, the need to navigate the tension between free will and determinism, and the Church’s relationship with the evolving scientific landscape have all played significant roles in shaping its approach to astrology. The Church’s responses to astrology have often mirrored contemporary societal attitudes towards science, reason, and the supernatural.

Looking towards the future, the relationship between astrology and ecclesiastical authorities is likely to continue reflecting broader societal trends and the ongoing dialogue between faith, science, and alternative belief systems. As contemporary society grapples with questions of spirituality, science, and the search for meaning, astrology may retain its appeal as a symbolic system that offers personal insight and a sense of connection to the cosmos. The Church’s future stance on astrology will likely continue to balance the historical and cultural significance of astrology with the core tenets of Christian faith.

In conclusion, the journey of astrology through the ages alongside the Church is a testament to the dynamic interplay between belief systems, cultural trends, and intellectual movements. As society continues to evolve, so too will the fascinating and intricate relationship between astrology and ecclesiastical authorities.

References and further reading:

- Barton, T. (1994). Ancient Astrology. Routledge.

- Brown, P. (1967). Augustine of Hippo: A Biography. University of California Press.

- Brooke, J. H. (1991). Science and Religion: Some Historical Perspectives. Cambridge University Press.

- Campion, N. (2009). A History of Western Astrology Volume II: The Medieval and Modern Worlds. Continuum.

- Grant, E. (1996). The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press.

- Hoskin, M. (1998). The Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy. Cambridge University Press.

- Katz, D. S. (1998). The Occult Tradition in the English Renaissance: A Reassessment. Continuum.

- Kieckhefer, R. (1989). Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press.

- Marrone, S. P. (1988). A History of Science, Magic and Belief: From Medieval to Early Modern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan.

- McGrath, A. E. (1999). Science and Religion: An Introduction. Blackwell Publishing.

- North, J. (1986). Horoscopes and History. Warburg Institute.

- Redford, D. B. (1992). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton University Press.

- Rochberg, F. (1998). Babylonian Horoscopes. American Philosophical Society.

- Shapin, S. (1996). The Scientific Revolution. University of Chicago Press.

- Tester, S. J. (1987). A History of Western Astrology. Boydell Press.

Thank you for reading.

Fuel my caffeine addiction and spark my productivity by clicking that ‘Buy me a coffee’ button—because nothing says ‘I love this blog’ like a hot cup of java!

Buy Me a Coffee

Your Astrologer – Theodora NightFall ~

Your next 4 steps (they’re all essential but non-cumulative):

Follow me on Facebook & Instagram!

Subscribe to my free newsletter, “NightFall Insiders”, and receive my exclusive daily forecasts, weekly horoscopes, in-depth educational articles, updates, and special offers delivered directly in your inbox!

Purchase one of my super concise & accurate mini-readings that will answer your most pressing Astro questions within 5 days max!

Book a LIVE Astro consultation with me!