No products in the basket.

Astro Philosophy: Free Will, Determinism, & the Causal vs. Reflective Nature of Astrological Interpretation

Dear NightFall Astrology readers,

Questions about the compatibility between free will and determinism have been a subject of fascination and controversy for centuries among astrologers and astrology enthusiasts alike.

The notion of whether one’s fate is predetermined or a matter of personal choice is a debate that has captured the interest of philosophers for millennia. The question of how astrology fits into this debate is a topic of much discussion.

So, let’s begin by defining astrology. It is the correlation between celestial alignments and earthly events. However, it’s essential to understand that astrology (in its original form when Babylonians invented it) is a system of signs, not causes. It does not make anything happen but reflects what is happening. Astrology exists because we live in a synchronistic universe with multiple layers of reality that can all reflect the same truth.

While some consider astrology to be somewhat predictive, I consider that it is wholly predictive. There is no way to fill in the gaps or negotiate with astrology. It is simply a tool for understanding what is around us. Astrology reflects our will, and we do not need to act against it. Planetary energies are not direct literal rays from planets but rather energies that correspond to what the planet represents.

It’s important to note that astrology is not something to blame or negotiate with; it’s merely a system of understanding. The natal chart reflects who we are rather than the cause of our behaviour. We mustn’t blame planets for our experiences; instead, we can use astrology as a tool better to understand ourselves and our place in the universe.

Moreover, it’s essential to understand that when we’re discussing “fate vs. free will” in astrology, we’re actually talking about “determinism vs. free will”. So let’s define the terms here:

(i) Free will is the ability to act at one’s own discretion without being compelled by fate or otherworldly forces. It doesn’t mean that we’re acting in a vacuum, completely unaffected by our past or personality. Rather, it means that we have agency, even amidst the various worldly influences that impact us.

One common misconception is that free will is equivalent to randomness, but this isn’t the case. The fact that we must pay taxes or adhere to other mundane obligations doesn’t diminish our free will. It’s simply a worldly influence that we have to contend with. Even if we were to choose not to pay our taxes, it wouldn’t negate our free will. We would still be free to make choices, albeit within the constraints of the potential consequences that come with not paying our taxes.

In essence, free will is about having the power to choose, regardless of the external forces that may influence us. While we can’t control every aspect of our lives, we always have the ability to choose how we respond to the circumstances we find ourselves in. By recognising the nature of our free will, we can take ownership of our lives and make choices that align with our values and aspirations.

(ii) Determinism posits that all events, including moral choices, are predetermined by preexisting causes. This belief suggests that with a full understanding of the laws of nature at any given moment, it’s possible to predict all future events. While many astrologers frame this as a debate between fate and free will, this is a misnomer since fate merely refers to the future, and the true dilemma is between determinism and free will. Therefore, the phrase “fate versus free will” is a categorical error.

In the following sections, you’ll see that historically, astrology has been used by the Babylonians as a system of omens or signals in the sky corresponding to earthly events rather than considering that the planets and stars are causing these events. This has been largely adopted by Hellenistic astrologers, too, to whom we owe our current practice of astrology.

However, I’m also including the few Hellenistic astrologers who viewed astrology as causal/affective and not reflective for the sake of a full and healthy debate. We’ll also be covering the question of whether events are partially or entirely pre-determined.

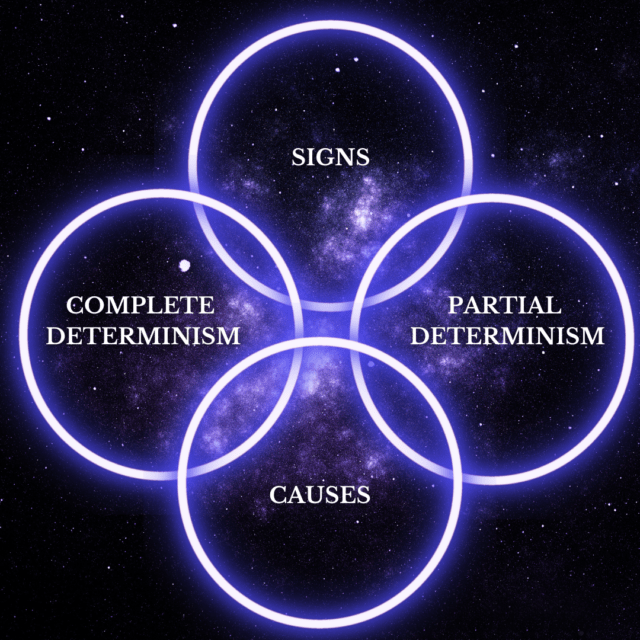

So, we end up with 4 different philosophical positions: (i) astrology is reflective and based on complete determinism; (ii) astrology is reflective and based on partial determinism; (iii) astrology is causal and based on complete determinism; (iv) astrology is causal and based on partial determinism.

These 4 positions are represented by the intersections between the circles in the Venn diagram (see the image below).

Finally, I’ll be explaining why I adopt the second position: astrology is reflective and partially deterministic (with a twist).

I. The original form of Ancient Astrology: an Astrology of omens & symbols

Astrology has been around for centuries and has a rich history. In the earlier Mesopotamian tradition, astrology was seen as a form of divination among many different forms of divination in the ancient world. Divination is the interpretation of natural phenomena as conveying symbolically significant information about events in the past, present, or future, and it’s usually understood as the attempt to ascertain information from the divine, especially to predict the future, by analysing the arrangement of randomly determined objects at the moment of the inquiry.

The Mesopotamian astrologers initially viewed the planets and stars as capable of sending messages to humankind from the gods about events that would occur. They believed that the celestial phenomena could act as signs of future events but were not necessarily the cause of those events. They saw the planets in the same way that a clock can indicate that it’s nine in the morning without being the cause of it being nine in the morning.

Later, the Mesopotamian view of celestial phenomena as signs of future events was passed on to the Hellenistic tradition. The interpretations of astronomical alignments became more complex due to the explosion of new techniques that were introduced, but the general principle remained the same: astronomical alignments were interpreted as having symbolic importance in a person’s life.

For example, the Midheaven or tenth house in a chart became associated with one’s occupation and reputation because it coincides with the sky’s highest and most visible part. The fourth house represents one’s home, living situation, and private life, since the fourth house coincides with the part of the chart under the earth and thus in the most hidden part of the cosmos from the observer’s perspective. This way, the part of the chart that is the most visible or prominent becomes symbolically associated with the native’s public life, while the part of the chart that is the most hidden becomes associated with one’s private life.

In Hellenistic astrology, symbolic reasoning is at the heart of many of the interpretive techniques. For example, Rhetorius (one of the most known Hellenistic astrologers to us from the 6th and 7th centuries A.D.) tells us that when one of the planets that represents marriage is hidden under the beams of the Sun in a person’s chart, the native’s marriage will take place in secret. The planet that represents marriage in the chart was visibly obscured and could not be seen with the naked eye at the moment of the native’s birth. Thus, it was symbolically thought to indicate that there is something about the native’s marriage that will be obscured or hidden as well.

Hellenistic astrology believed that the alignment of the planets at the beginning of something, known as “katarche,” could predict its outcome, known as “apotelesma.” This idea had already been developed in the Mesopotamian tradition by the fifth century B.C. with the concept of the birth chart. The technical term “katarche” meant “inception” or “beginning,” while “apotelesma” meant “outcome” or “completion.” This “if x then y” formula became the basic premise of Hellenistic astrology, which was partially developed as a type of divination.

II. Causal/affective astrology?

At another point during the Hellenistic period, some astrologers began to see the planets as causes of future events. This view became popularised in the work of Claudius Ptolemy, a second-century astrologer. Ptolemy believed that the planets could influence events and people on Earth because they produced different elemental powers in the sublunar realm, drawing on Aristotle’s four primary qualities of hot, cold, wet, and dry. For instance, Mars was believed to cause anger or brashness, and Saturn was associated with sluggishness and depression. In Ptolemy’s view, astrology was an extension of physics, and he emphasised the naturalistic rationale for basic concepts. However, earlier astrologers had used more symbolic rationales for some doctrines. Aristotle had formulated a general theory of celestial influence, where the rotations of the planetary spheres were seen as the ultimate source of all motion or change on Earth. This view was elaborated on by followers of Aristotle, known as Peripatetics.

In the first century A.D., some writers started linking certain qualities of heat and moisture with planets. Pliny, the Elder and Dorotheus of Sidon, described some planets as hot, cold, or somewhere in between. This confirms that Ptolemy’s ideas about celestial causation were not entirely new. However, Ptolemy took the causal view of astrology further than his predecessors, and his ideas are often seen as definitive for astrology in the Greco-Roman period.

David Pingree (January 2, 1933, New Haven, Connecticut – November 11, 2005, Providence, Rhode Island, an American historian of mathematics in the ancient world) argued that planetary causation was the primary difference between Hellenistic and earlier Mesopotamian astrology. However, there is evidence that sign-based astrology persisted into the Hellenistic tradition, and there was a debate about the mechanism underlying astrology in the mid-first century A.D. Different astrologers had differing views about why or how the system worked, so there’s no reason to restrict the definition of astrology to just the causal view.

The second issue with Pingree’s argument is that although Ptolemy’s view that planets cause events became dominant after he published Tetrabiblos in the mid-second century, the debate about whether planets cause events or just signify them continued for centuries both inside and outside the astrological community. The philosopher Plotinus, for instance, argued against the idea that planets cause events in his works “On Fate” and “On Whether the Stars are Causes”, saying that the planets simply signify events like letters signify words.

Similarly, in the fourth century, Sallustius argued that events before the moment of birth cannot be caused by the planets’ conjunction at the moment of birth, but are only signified. Moreover, in the fifth century, the astrologer Hephaestio of Thebes acknowledged the two different conceptualisations of astrology – whether planets signify, cause or encircle events.

Eventually, during medieval times, the idea that planets cause events became the most widely accepted view of astrology. However, some other practices, like interrogational astrology, still relied more on signs. It’s interesting to note that some scholars, like Campion, believe that Ptolemy’s causal approach actually helped astrology survive during the medieval period because it made astrology seem more like a natural science and less like divination. This way, astrology was able to avoid some of the religious opposition that it might have otherwise faced.

III. Astrology & Stoicism: love your fate (amor fati)

People who practice astrology have different ideas about whether our lives are predetermined or not. Astrology was first developed in Mesopotamia a long time ago, when people didn’t know as much about astronomy (the study of space and celestial objects). As people learned more about astronomy, they discovered that the positions of planets and stars were actually predictable and predetermined. This led to the idea that events on Earth might also be predetermined. The philosophy of Stoicism, which was popular around the same time as astrology in ancient Greece and Rome, taught that everything that happens is predetermined as part of a divine plan. This idea of fate was appealing to people who wanted to know what would happen in their lives, and astrology became a popular way to try to figure that out. Astrology was seen as a way to prepare for the future so that people wouldn’t be caught off guard by good or bad events. This was a common idea among astrologers, even though they had different ideas about how astrology worked.

For example, Valens (one of the top Hellenistic astrologers to whom we owe the restoration of most of the traditional predictive techniques thanks to his “Anthology” book) says:

“For God, in his desire that man should foreknow the future, brought this

science into the world, a science through which anyone can know his fate

in order to bear the good with great contentment and the bad with great

steadfastness. […] Accordingly then, the initiates of this art, those wishing

to have knowledge of the future, will be helped because they will not be

burdened with vain hopes, will not expend grievous midnight toil, will

not vainly love the impossible, nor in a like manner will they be carried

away by their eagerness to attain what they may expect because of some

momentary good fortune. A suddenly appearing good often grieves men

as if it were an evil; a suddenly appearing evil causes the greatest misery to

those who have not trained their minds in advance.”

He proceeds to stress that people who predict the future and seek the truth (namely astrologers) have attained freedom of the soul and don’t place much value on fortune, hope or fear of death. They live calmly, training their souls to be confident and maintain contentment with what is present. By mastering themselves and being detached from pleasure or praise, they are capable of bearing what is preordained, becoming “soldiers of fate”.

According to Firmicus (another famous 4th-century Hellenistic astrologer), studying astrology helps us develop a mindset that despises both good and evil in human affairs. This is because we become aware of upcoming difficulties and are better equipped to face them without fear. With a strong and stable mindset, we can’t be oppressed by bad fortune or overly excited by the promise of good fortune.

In his astrological work, even Ptolemy acknowledges that foreknowledge helps train the soul to accept arriving events with peace and tranquillity, even for events that will necessarily result. This sentiment is echoed by other authors, including Hermes Trismegistus and Zoroaster, who suggest that philosophers are superior to fate because they are not swayed by pleasure or pain, and they look towards an end of ills. These ideas may have originated from influential foundational astrological texts of the Hellenistic tradition.

By the second century A.D., fate and astrology had become almost interchangeable concepts. While Stoicism may have popularised the idea of accepting one’s fate, astrology was seen as the means of studying it. Astrologers such as Manilius, Firmicus, and Valens explicitly stated that their role was to study and explain the fates of men. In Hermetic texts, the planets were described as instruments of fate, governing the sensible world in circles. The association between fate and astrology became so strong that arguments against one were often arguments against the other.

IV. To what extent are events predetermined from Astrology’s perspective?

Astrology’s purpose is to study a person’s fate, but the extent to which fate is predetermined has been debated among astrologers. Some believed everything in a person’s life was predetermined, including their internal motivations and choices, while others held different views. This created a spectrum of positions, with the most deterministic end being the belief that fate rules the world and nothing can be changed. This view was expressed in Stoic philosophy as the doctrine of internal and external fate and in astrology in Book Four of Manilius. Fate determines everything from a person’s skills and character to their successes and failures, and there is no escaping one’s appointed lot.

Manetho expressed a similar idea in poetic verse that the nativity of men cannot be altered, as the threads of fate bind it with unbreakable strings and iron spindles. Many Hellenistic astrologers tended to hold deterministic views, as evidenced by the abovementioned statements made by Valens and Firmicus. However, not all astrologers’ views are clear, as surviving texts are mostly technical manuals with brief philosophical digressions.

On the other hand, some astrologers believed that fate was only partially predetermined and that it could sometimes be negotiated or mitigated under certain circumstances. Evidence suggests that Mesopotamian astrologers were not entirely deterministic in their worldview, as they practised apotropaic or propitiation rituals to dispel bad omens. This belief continued into the Hellenistic tradition, where magical and medical texts contained remedies for treating or countering certain conditions. Ptolemy used a medical analogy to explain that seeking treatment for an illness could mitigate or cure it, similar to how the influences of planets could work. There are also references to spells that could free individuals from their astrological destiny or change fate through magic or ritual. However, it is unclear what every astrologer’s views were since most surviving texts are technical manuals, and the philosophy of astrologers had to be reconstructed from brief digressions interspersed throughout the texts.

Zoroaster (the famous ancient Persian prophet) also believed in using knowledge of supernatural things and Magian science to avoid the evils of fate, while Hermes believed that a spiritual person need not rectify anything through magic and should allow fate to work in accordance with its nature. Ptolemy rejected the hard-line deterministic view of astrology, saying that not every single thing is ordained for each individual from the beginning by divine ordinance and that other causes can counteract it.

{ Side note: it is crucial to keep in mind that the practice of the occult science of Magick to “alter one’s fate” is strictly reserved to its adepts and initiates, and CANNOT be practised by the average individual who’s very early on the path towards enlightenment. Such practices can have catastrophic consequences in a person’s life if they lack the needed high-level knowledge, chastity, and morality when engaging in them. }

Nevertheless, Ptolemy argued that celestial influences are not always immutable and that while some global events cannot be avoided, there are certain things that can be done on a smaller scale to mitigate astrological influences. He stated that occurrences with a first cause that is greater than any counteracting cause will always result, but occurrences without such causes could be easily reversed. Ptolemy’s views were influenced by his quasi-Aristotelian cosmological beliefs.

Firmicus criticised the moderate or conditional determinism advocated by Ptolemy, arguing that admitting the necessity of fate and then denying it was inconsistent. Some Hellenistic astrologers, such as Dorotheus, viewed fate as conditional or malleable to some extent and gave rules for inceptional astrology, which involved selecting specific times to begin undertakings to ensure a more favourable outcome. However, Augustine specifically criticised the idea that one could use inceptional/electional astrology to alter one’s fate.

In sum, astrologers in ancient times debated whether planets and stars acted as signs or causes and whether events in the world were completely or partially predetermined. These debates resulted in the establishment of four fundamental philosophical positions (the four intersections), which can be seen on the Venn diagram (see the image below).

Ptolemy falls in the overlapping area between causal astrology and partial determinism, while Firmicus viewed everything as completely predetermined. The third and fourth positions involve those who saw the planets as signs or omens of future events rather than causes. Valens saw the planets as signs but advocated a more deterministic philosophy, while Dorotheus used symbolic techniques but may have viewed fate as malleable.

The ancient Hellenistic tradition established these four fundamental philosophical positions about astrology, which have endured for over two thousand years. Understanding these positions is crucial because they shape how astrologers view their lives and interpret clients’ charts. This knowledge also informs the presentation of astrology as a subject.

V. Concluding (personal) observations:

Upon reviewing the various philosophical stances on the perennial debate between determinism and free will, and between reflective and affective astrology, one overarching question looms large: are determinism and free will reconcilable?

The teachings of St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) assert that celestial bodies exert influence on the material realm but leave the rational soul and free will untouched. My viewpoint follows his stance, only I tend to adopt that astrology is reflective not affective. Therefore, even in a universe where astrology could be viewed as a deterministic signal (rather than an influence) for earthly events, the agency and rationality of human beings remain intact.

The idea of free choice resonates with Aquinas’ perspective, suggesting that we act autonomously within the boundaries of the world and Divine Providence. While our actions are not arbitrary but discernible and explicable, they still stem from our free choice and not from celestial determinism.

The application of advanced astrological techniques such as Zodiacal Releasing may imply a deterministic layout of one’s life events, yet Aquinas would argue that this cannot infringe upon human free will. Astrology, then, functions more as a mirror reflecting potential rather than a deterministic force compelling outcomes. These celestial signals operate under God’s ultimate providence and cannot contravene our God-given agency.

Astrology doesn’t determine but rather signifies, much like a clock displaying time without altering it. This distinction clarifies that astrology doesn’t interfere with human free choice; instead, it serves as a reflection of potential life trajectories within the bounds of Divine Providence.

As our comprehension of astrological correlations evolves, our predictive capabilities may improve, yet these should not be mistaken for negations of free will or agency. The advancements in astrology may someday allow us to pinpoint specifics, like dates or meals, but they won’t change the basic premise: our fate may be signalled but not forced. Astrology, even in its most deterministic interpretation, doesn’t negate our ability to make choices within a predetermined framework governed by God’s will.

In summary, while astrology provides a compelling layer of understanding concerning life’s potentialities, it doesn’t infringe on our agency. The celestial bodies may mirror the material world but cannot dictate our rational choices. At the end of the day, it’s not astrology but God who has the ultimate say in our lives, ensuring that while our fate may be foreseeable, it isn’t unalterable by our actions (not magical remedies as seen by the ancient astrologers who were advocating for the partial determinism position) in alignment with the word of God. Astrology offers a lens into life’s possibilities, but these are always subject to Divine Providence.

References and further reading:

- Aquinas, Thomas, “Summa Theologica”, Translated by the Fathers of the English Dominican Province. New York: Benzinger Bros., 1947.

- Brennan Chris, “Hellenistic Astrology: The Study of Fate and Fortune”, Amor Fati Publications; First Edition (February 10, 2017).

- Dorotheus of Sidon, “Carmen Astrologicum”, translated from ancient Greek by David Pingree in 1976, Astrology Classics (August 1, 2005).

- Pingree Edwin David, “From astral omens to astrology: From Babylon to Bīnāker”, Herder, International Book Centre (January 1, 1997).

- Rochberg Francesa, “The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture”, Cambridge University Press; 1st edition (October 29, 2007).

- Ptolemy Claudius, “Tetrabiblos”, Forgotten Books (November 16, 2016).

- Valens Vettius, “The Anthology“, Mark T. Riley’s translation from ancient Greek, Amor Fati Publications (October 16, 2022).

Thank you for reading.

Fuel my caffeine addiction and spark my productivity by clicking that ‘Buy me a coffee’ button—because nothing says ‘I love this blog’ like a hot cup of java!

Buy Me a Coffee

Your Astrologer – Theodora NightFall ~

Your next 4 steps (they’re all essential but non-cumulative):

Follow me on Facebook & Instagram!

Subscribe to my free newsletter, “NightFall Insiders”, the place where the most potent magicK happens, and get my daily & weekly horoscopes, exclusive articles, updates, and special offers delivered directly to your inbox!

Purchase one of my super concise & accurate mini-readings that will answer your most pressing Astro questions within 5 days max!

Book a LIVE Astro consultation with me!